I met a map-maker once, years ago, on the west coast of Ireland. He was not like other people I had met, he seemed like a monk to me, and it felt comfortable as I had just finished studying philosophy for a few years in University and monks, mapmakers, and philosophers can share a disposition. The map maker reminded me of so many people I had studied. We would sit and talk and drink tea in his office, a light infused room at the end of a pier in the village of Roundstone; and I knew it was special.

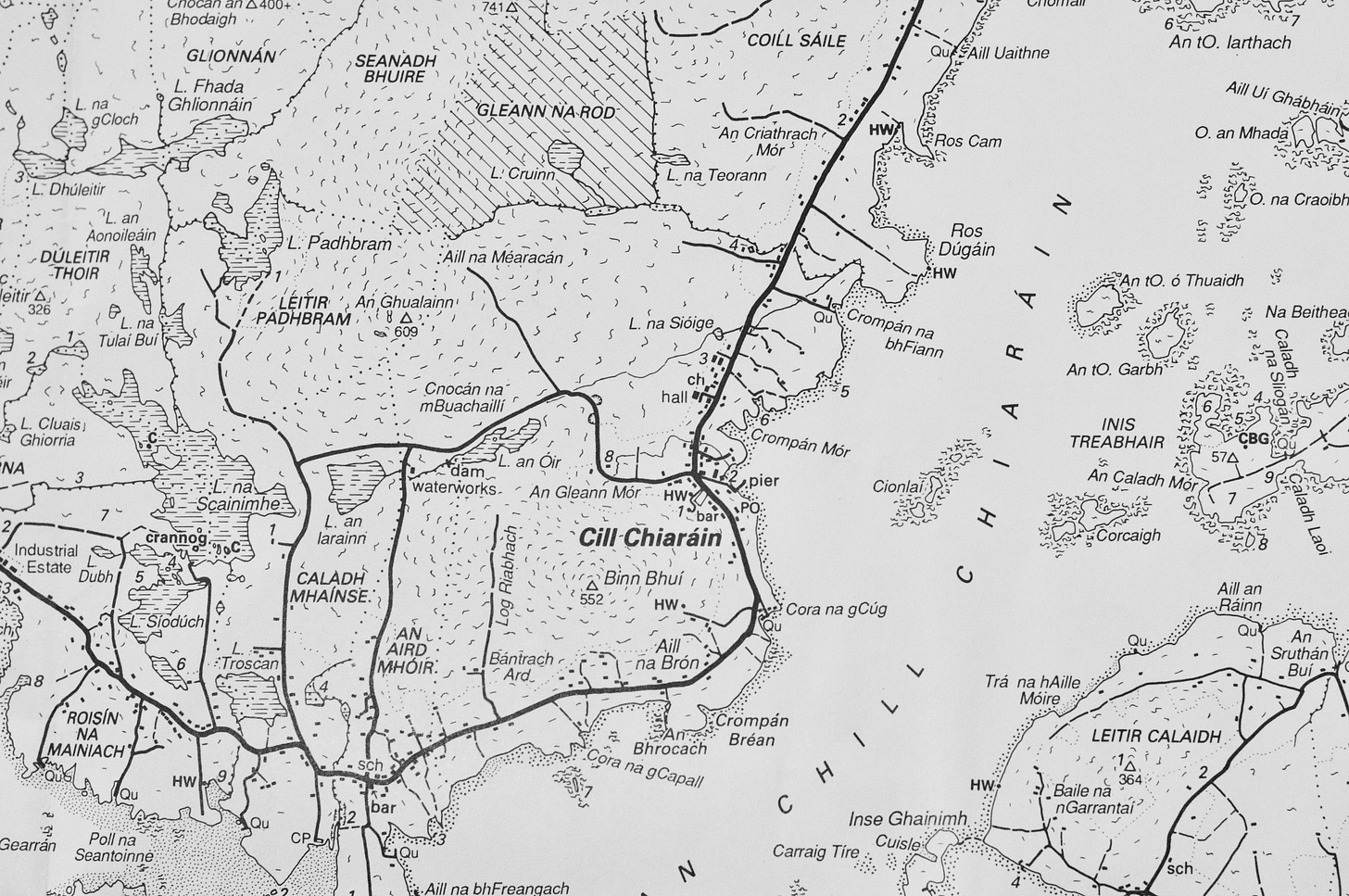

Tim was originally from Yorkshire, a mathematician, at first, then, a successful artist in a time when geometric figures were in trend (there are pieces of his at the Tate Modern – he went by the name Timothy Drever then, later returning to his full name, Timothy Drever Robinson). A mathematician’s mind creating beautiful scenes from fractal geometry. A life of seemingly large shifts but all on theme with mathematics, beauty, and chaos. Then, in another shift, he picked up and moved off the coast of Galway to the Aran islands. It was 1972. There he found the merging of his worlds on the shores of rock, swirling coastal lines constantly shifting with the waves and the tides. His mind wanted to know more about the landscape and he searched for maps. He found the most accurate maps made were Ordnance surveys that had been drawn by an institution not familiar with the way of Irish topography, and were last updated in the early 1900’s. The maps had anglicised versions of names which carried no weight of meaning to them, no context, white noise; zero of information-content. Robinson wrote “Irish place names dry out when anglicised, like twigs snapped off from the tree,” and he became interested in mapping the landscape with all the complexities of personal history of a community. This was no easy task as he was not from there, but ever committed, Tim started to walk, and talk, and mostly listen and then began marking notes on a page. It became a new art piece that was to last over 40 years. He produced hand drawn maps of the Aran Isles, the Burren, and Connemara; but single map sheets not being enough to tell the stories of the places, he also wrote page after page about the mapping and stories of the landscape, translating what he was hearing in the homes and pubs of the countryside. These writings became a series of books on the region; two books on the Aran Islands, and three on Connemara. Together with the physical maps he drew, one would have the topography as well as the context of communal history. Tim’s writing was an attempt to lock in the language of the place in the naming of things. Place names locals used were beginning to be lost, and in the names were the understanding of time and space of the landscape, was the landscape itself in the tempo and cadence of the words.

The below is a story I first heard from Tim and it stuck inside my head and sits there still. It is a story he dug up from an old book he found in a London Library, a pastime we shared, the browsing of bookstalls and jumble-sales. The book was The Saxon in Ireland by John Hervey Ashworth, published in 1851. This section of the book was titled The Echo Hunter. I put it here for a two reasons.

One: its beauty, the idea of shifting the definition of an echo to be personal and natural and secret.

Two: things like this, stories of place from some recessed time, are gold to me. I am setting off in March for a research trip in Ireland, and I fully intend to seek out the places discussed below, if only to feel the vibrations in hopes that there is a bit of magic still in the air.

The Echo Hunter

I was at Ballina, on my way into Donegal, where it was my original intention to settle. In the evening of a sultry day, I was sitting at the open window of the inn when the melodious sounds of a bugle, playing a beautiful Irish air, attracted my attention. Nothing could be finer, and, in the then state of my spirits, more affecting; but it soon ceased, and I sat motionless, full of those sad and melancholy feelings which such music will call forth.

No long time had elapsed when a little, dapper-looking gentleman of middle age entered the room with a bugle in his hand.

“I have to thank you, sir, I presume,” said I, rising and bowing, “for the great treat I have just enjoyed?”

“You have to thank me for very little, sir,” replied he carelessly, “but if you are really fond of this kind of music, it may be in my power to give you some gratification. This instrument,” continued he, “is all very well, but I seldom use it except to awaken a finer music still.”

I stared, for I did not at first quite comprehend him.

“Sir,” continued he, “I use this bugle to awaken Dame Nature, whom you will find sleeping among the crags and cliffs. The moment I sound my bugle, an answer comes from the mountains, no less singular than it is beautiful—leaping from rock to rock, now loud, now murmuring, but always sweet, till it dies away in echoes, low and fine as the gentlest wailings of an infant.”

“Excuse my dullness,” said I, smiling. “I understand you now; you mean the echo?”

“Why, yes,” he replied, “echo, according to the common language of the world. I call them the voice of awakened Nature. There is nothing in the theory of sound that can satisfactorily account to me for the wonderful voices my bugle has awakened in certain spots which I have discovered; but I do not make them generally known, for—laugh if you will—I have a notion, which I like to encourage, that Nature loves solitude and would ill brook being disturbed by every common idler.

"I have travelled through and through Ireland, meeting with such echoes in many a sequestered nook, unnoticed by anyone before me, and the result with me is this: Donegal exceeds even Kerry in one particular spot; Kerry exceeds Clare—but Ballycroy, yes, sir, not twelve miles from hence—Ballycroy exceeds them all.”

By way of epilogue to this strange tirade, he put the bugle to his lips and played rapidly, but in lower notes than I conceived the instrument capable of, a very lively Scotch air, in the style of Neil Gow, proving himself a perfect master of the art.

“Well,” thought I, “we are all slightly mad upon some points, or there is no truth in old saws, and my new friend is evidently not exempt from so general a law of nature. But he is evidently a man of talent and information, and it shall not be my fault if I do not profit by his acquaintance.”

Accordingly, I drew him out to the utmost of my power and was well rewarded. There was not any part of Ireland, Scotland, or Wales with which he was not familiar. He had visited Switzerland too, but the mountains and valleys there, he said, were on too vast a scale for his purpose. In Merionethshire and Snowdonia, and other parts of North Wales, he had been very successful, as also in the western Highlands of Scotland; but it was in the wilder districts of Connaught and Munster that he most delighted.

In Glen Inagh, not far from the head of Kylemore Lake, at the foot of Mulrea Mountain, near the Killeries, on the western side of Croagh Patrick, and in Ballycroy, near the lake of Carreg-a-biniogh, and in a spot between Corselieve and Nephin Beg mountains, he had awakened, he said, responses that might almost be thought superhuman. The valleys and cliffs seemed to start into life, and their voices were lifted up as if they were living things.

“But,” said he, lowering his voice, “it were vain for you or any other mortal to attempt to find out these peculiar spots. I alone discovered them, and with me the knowledge of their existence will die. As no living man has the powers of invitation that I possess, so is it vain to expect from Nature a similar response. It cannot be.”

I readily assented to this assertion, being, of course, quite convinced that the response of the echo must be more or less wonderful according to the skill of the musician.

My companion was in all respects a gentleman, was a first-rate judge of the laws of harmony, knew the merits and demerits of all the principal composers and artists of the day, intermingled many interesting anecdotes with his disquisitions, and criticised with taste and learning.

Ere we parted for the night, he invited me to accompany him on the following morning on an excursion into the Ballycroy mountains; and it was in this valley, not very far from the spot in which we are now sitting, that he gave me a specimen of his powers of “awakening the voice of Nature.”

He placed me on a certain spot, and, exacting a promise that I would not follow him, he retired, and in about a quarter of an hour gave me such a treat in his peculiar art as I can never forget. To describe it is impossible. No band of instrumental music in the world could equal it.

The reverberations were perfectly astounding. The rocks and mountains seemed alive with the soul of harmony; the softest and wildest notes floated on the air—now close, now distant; now dying away in some distant recess of the valley, now awakening louder and louder among the cliffs and precipices; at one moment faint as the whisper of the breeze, at another loud, clear, and bold as the trumpet of the Archangel.

“But,” continued Mr. S—, smiling, “I dare say by this time you think me as enthusiastic as my friend. Certainly, I never before or since have experienced the sensations which at that time overpowered me, and I no longer either smiled or wondered at the zeal of my new acquaintance in his peculiar and eccentric pursuit.

I never saw him afterwards but once, nor could I ever discover the exact spot from whence this astonishing echo could be produced. That it is within a quarter of a mile of this spot, I am convinced; and when I last caught sight of him, he was leaning pensively against the rock, round whose base we turn on entering the glen below us.

Our greeting was short. He congratulated me upon my improvements, but declared significantly that ‘Art would drive out Nature.’

“This,” he said, “is my last visit to this valley. It was once a favourite spot of mine, but the presence of man has tainted it. In Corranabinna, I am safe from intrusion. There, man will never pitch his tent; it is too near the sky; and let me tell you, sir, Nature speaks there in a language that even these rocks could never equal.”

I could not prevail upon him to accept the rude hospitalities of my cottage, and, after we had parted about ten minutes, a few discordant notes of his bugle awakened a thousand more discordant echoes, and I never saw him more!