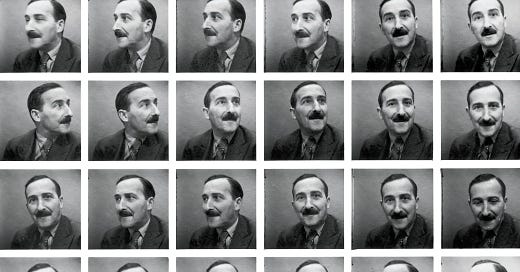

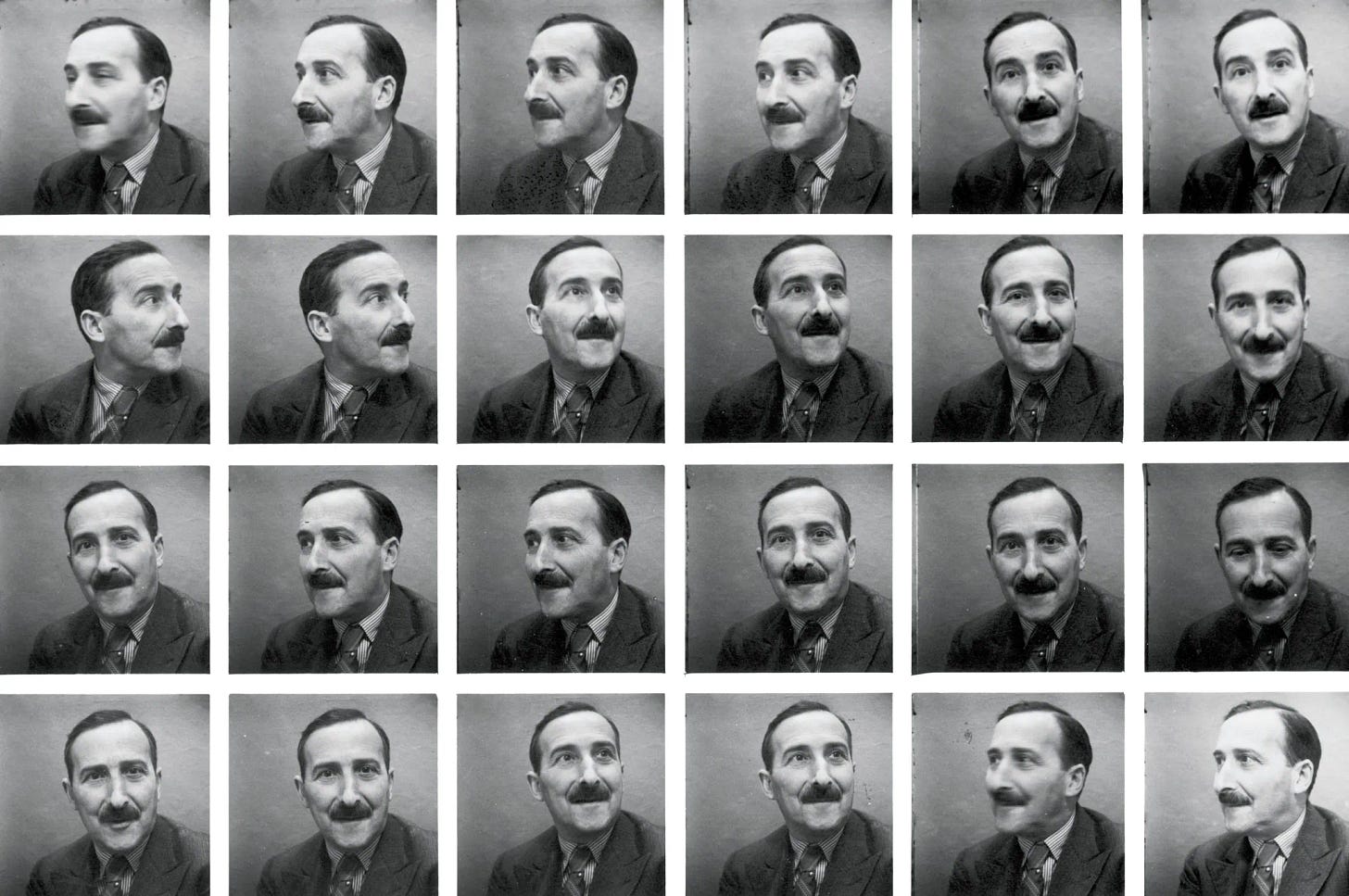

“To Travel or be Travelled” is a 1926 essay by Austrian author Stefan Zweig. He was a popular writer during the 1920s and 1930s, especially in the U.S., South America, and Europe. He produced novels, plays, biographies, and articles. Zweig studied in Austria, France, and Germany before settling in Salzburg in 1913. In 1934, driven into exile by the Nazis, he emigrated to England and then, in 1940, to Brazil by way of New York. He was also one of the inspirations for Wes Anderson’s “Grand Budapest Hotel” both in tone and timbre.

Stations and ports, these are my passion. For hours I can stand there awaiting a fresh wave of travellers and goods noisily crashing in to cover the preceding one; I love the signs, those mysterious messages that reveal hour and journey, the shouts and sounds dull yet varied that establish themselves in an evocative ensemble of noise. Each station is different, each distils another distant land; every port, every ship brings a different cargo. They are the universe for our cities, the diversity in our daily life.

But now I see a new kind of station, and here in Paris for the first time; they stand in the middle of the street, without visible lobby or roof, there is nothing distinctive about them and yet they are the focus of an unrelenting tide of activity. This is the stop for automobiles destined for group travel, which one day perhaps will take over from the railcar: with them commences another kind of travel, travelling en masse, contractual travel, or being 'travelled'. Nine o'clock: the first detachment arrives from the boulevard, forty or fifty passengers, mostly American and English. An interpreter sporting a gaudy cap loads them into the vehicle, they are taken to Versailles, to the Loire chateaux, to Mont St Michel, even as far as Provence. For them a mathematical organization has thought of everything in advance, prepared everything; they need search for nothing, figure out nothing; the car starts, they depart for a foreign city, lunch (included in the price) awaits them there, as does a bed for the night; museums, wonders are entirely at their disposition on arrival. Needless to hail a porter, to give a tip. For every gaze, a time has already been worked out in advance, the choice of journey is the fruit of long experience: how simple it all is! No need to worry about money, to prepare oneself, to read up from books, to go in search of lodgings - and behind these 'travelled' (I don't say 'travellers') stands, with colourful headwear, the guardian (because in a sense he is both a guard and a watchman), who mechanically explains to them each particularity. The sole movement required is to present oneself in a travel agency, to choose a destination, pay the required amount, purchase board and lodging of some description for fourteen days, as already your luggage precedes you and brownie functionaries have organized bed and breakfast at some unknown place - and thus, without lifting so much as a finger, thousands upon thousands of travellers arrive from England and America. Or the 'travelled', to be more precise.

I strive to imagine myself one day in the midst of such a group. The air of convenience surrounding the whole affair is undeniable. All the senses are marshalled for contemplation and pleasure: one's attention is not deflected by those Lilliputian worries, constant vexations over the search for shelter and lodgings, one is not obliged to consult railway timetables, one does not stumble into streets where one has no right to be, one does not put oneself in a position to be scoffed at, cheated, to stammer, knowing barely a few words of the foreign language - all the senses are primed exclusively to embrace novelty. Novelty, which, having passed through the sieve of several decades of experience, is reduced to mere curiosities: one only sees the bare essentials in this kind of group travel, company is always missed by those for whom pleasure is only effective when shared with others. Furthermore, it's good value, practical and above all easy - therefore the shape of things to come. One no longer travels, one is travelled.

And yet, is it not the most mysterious aspect of travel that will be lost in such a fortuitous arrangement? Since time immemorial, there has floated around the word 'travel' a whiff of danger and adventure, a breath of capricious chance and engrossing precariousness. When we travel, it's not only for the love of far-off lands; we also want to leave our own area be-hind, our domestic world so well regulated day to day; we are drawn by the desire no longer to be at home and therefore no longer to be ourselves. We want to interrupt a life where we merely exist, in order to live more. So, to be 'travelled' in this manner, one must be content to pass before numerous novelties without actually experiencing them at all; all the strangeness, the distinctiveness of a country will utterly escape you as soon as you are led and your steps are no longer guided by the real god of travellers, chance. In fact, in their group automobile, these English and Americans remain in England and America, they never hear the native language, they have no consciousness of specificity and the customs of the people (for all friction is dismissed). They see things worth seeing, certainly, but twenty car loads daily see the same wonders, each sees what the other sees and the guide who is responsible for providing explanations always offers the same method of delivery. And no one feels it deep within, because it's a group; beneath a swell of words they approach those lofty values and most noble worlds, but they are never alone to observe, to spiritually absorb these marvels: what they take home is nothing but the righteous pride of having recorded with their eyes some church, or painting - more a sports record than the sense of any personal maturation and cultural enrichment.

Surely it is preferable then to accept the unpleasant, the difficult, the contrary aspects: for these make any travel experience worthy of the name; there is always a contradiction between comfort - an objective reached without sufferance - and the truthful lived experience. The vital component in life, all that we consider a gain is the fruit of an effort and of a resistance, all genuine intensification of our relationship with the world must in some way be united with the personal fibre of our being. That's why the ceaselessly perfected mechanism of travel seems to my mind more dangerous than beneficial for anyone who is not content to approach the unknown only at its exterior point, but seeks to reach into their soul for the truly powerful and vital image of a new landscape. There where we do not discover, or at least do not believe we will discover, where no concealed energy or fellow feeling drives us towards novelty, we miss a mysterious tension in the enjoyment, a link between the undisclosed and our incredulous gaze; and the less we allow experiences to reach us with casual ease, the more we will approach them in the true spirit of adventure and the more they shall be intimately grafted onto our being. The mountain railways are a marvellous accomplishment: in an hour, they can whisk you to the most awe-inspiring world; without fatigue and in considerable comfort, one may savour the panorama sloping away at one's feet. However, such a mechanical ascent deprives one of any physical stimulation, of that uncanny fizz of pride that accompanies the sense of conquest. They are deprived of this remarkable feeling, inherent to every true experience, all those who are travelled rather than travel, who, as they take out their wallet at the kiosk to pay for some tour, do not pay the higher price, the more valuable one: that of the inner will, the tension of its energy. The odd thing is it's precisely such a cost that will be reimbursed thereafter with the greatest extravagance. Indeed, only those impressions acquired through vexations, annoyances, mistakes, leave us with a clear and vibrant memory. We like nothing better than to recall the minor woes, the nuisances, the muddles and the mistakes brought about by travel, as when, approaching our twilight years, what we really hold dear to our hearts are the most foolhardy exploits of our youth. Our day-to-day lives follow the ever-more mechanical and stringently smooth ride upon the rails of a technologically seduced century, something we cannot prevent and perhaps don't wish to anyway, for this way we conserve our strength.

But travel must be an extravagance, a sacrifice to the rules of chance, of daily life to the extraordinary; it must represent the most intimate and original form of our taste. That's why we must defend it against this new fashion for the bureaucratic, automated displacement en masse, the industry of travel.

Let us preserve this modest gap for adventure in a universe of acute regulation. Let us not hand ourselves over to these overly pragmatic agencies who shepherd us around like goods, let us continue to travel in the way our ancestors did, as we wish, towards the goal we ourselves have chosen. Only that way can we discover not only the exterior world but also that which lies within us.

A timely reminder. Thanks for giving Zweig to us.