tis of thee

on the majesty of a wild river, citizens, and the legal definitions of what it means to be a person.

I am a part time professor which means I teach one course a semester. I enjoy it immensely. The relationship of a dynamic classroom is something so wonderfully human in the best of ways. It is a community of minds working on the same issues of understanding simultaneously, it is the dialectic incarnate. I tend to bend any and all classes I teach into some sort of lesson of anthropology. It makes sense, I teach about travel which is the education of an anthropologist. A few weeks ago my students asked me if I wore boots when I taught because I was American. I live and teach in Toronto, and most of my students are international. There was an impression that I was advertising my Americana through my boots, which both made me laugh and stopped me in my tracks because, I think, in part, they were right. Subconsciously I wanted to place myself as the southerner in the North, the slightly askew.

I have always been geographically confused, not fully of a place, not fully committed. I was born in California but lived in New Jersey until I was 7, then a farm in Georgia. West Coast, East Coast. North and South. I have always felt part of something larger than a state, or nation, or hemisphere. Or perhaps something smaller. There were times in my youth where I would see places become an enemy through geography. Atlanta was always talked down to from all the places around Atlanta. The big city, city-folk putting on airs. God help you if you were from the North or New York. But I never felt the impulse, I was attracted to that strange beast of the south, the urban southerner living in Manhattan. Truman Capote, William Faulkner, Harper Lee. Some of these dramatically wore their southerness in their clothing as well, they wore their boots.

I became a citizen of Canada a few years ago. I have two passports now, from two countries. Some think I am no Canadian, but of course I always will be. I had to take a test on what it means to be from here, I had to swear allegiance to a King like some old story book. It didn’t feel real but in the same way a passport seems silly to me. I hear a lot about patriotism as an immigrant. What it means to be from here or there. In all of this I have been accused of lacking Americaness, that I am no American, but of course I always will be. That I am only half American and half Canadian, but community isn’t as binary, human relationships rarely are, and I am fully both. I fear something has been confused in all of these terms the past few years; patriot, nation, citizen.

We are pack animals but the pack can only be a certain size before the idea is abstracted and morphed, before it becomes wonky. Virtual communities are something different from what I am talking about. Virtual communities are selective times, a branding or presenting of oneself happens. Whereas in my neighborhood there is no presentation when I run out of my house in my undies with a trash bag I forgot to put on the curb. The daily passing of the same people I might not know their names, but I see more often than my brother or mother. This vague connectivity I see as part of a definition characteristic to real life physical non-virtual community. There is something so essentially and passively human about these connections that I think might just be building blocks of what it means to be citizen, to be of a place. To physically just be there.

The concept of citizenship in ancient Greece (Politeia, which meant dweller of a city or community) was generally limited to property owners. Citizens in Greek city-states had the right to vote, it went hand in hand. Populations were a lot smaller then, cities were smaller, and city meant, and still means, something smaller than country. Property owning voting members of a community thought of as citizens; legal terms defining what it means to be a full fledged human in a place. If you own property, you have rights as a full citizen. If you do not, you are not a full citizen, you are not fully part of the place, not fully human. This process of defining personhood, or humanness, isn’t some antiquated past of ours, we still do this, we still are defining and excluding.

In 1902, it was debated in parliament in Australia as to whether Aboriginal people were human beings. The right for women to vote in the USA was not secure until 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment. There are currently, the largest numbers in our global history of people who have migrated and pay taxes in a place, live in a place, serve as community members but are not recognized by the local, provincial, or federal governments as full people; can’t vote, can’t own property.

At the same time, there are groups of humans who are defined as a person, have rights as a person, and move in a similar way on paper. This is an old concept, one that is at the foundation of looking at the masses as both the one and the many. A body of constituents. In a strange way, this is the heart of the central idea of any governing system, the relationships between the elected and the electors, one to represent the many, the constant balance of the group and the individual.

Post civil war in the USA, the 14th amendment stated that “No State shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” A statement built for post war USA, a law opening up the opportunity for recognition of a whole set of people previously not defined as human beings, those stolen from African shores and enslaved in the industry of North America. But the law was shifted and deformed into something else with the case in 1882 of San Mateo County v. Southern Pacific Rail Road, a case that would allow for the opening of the idea that a corporation is a person in the eyes of the law, the concept of Corporate personhood. This would later be expanded in 1970 to equate the use of money with the legal structures built around free speech, which would then later be expanded in the Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission case in 2010, which would blast through that door with free speech money being used without limit on elections by persons (which are equated with corporations in this language, person = corporation). Legal parlance aside, in a long about way, the laws created to help protect the rights of the previously enslaved were used in order to give corporations the right which now allow for large amounts of money to be used to effect elections.

This was not the first of its kind, it had been done before. Organized religions had extended certain rights to corporations or institutions in the past, mostly to avoid property loss and bolster concepts of property ownership. The Catholic Church had an issue with property being owned by one person, and if that person died the property would become renegotiated or sold, so ownership was given to sets of people instead, to a community, a similar concept of individual rights extended to groups of people. Locomotive Corporations had the same issue post civil war in the USA, the want and need of a business to own the land as opposed to an individual, to ensure the railroad would be owned completely from one coast to the other for longer than a lifetime.

These relationships of property, place, citizenship, flesh and blood personhood and humanness, all have been swimming in my head these past few months. This legal fluidity of personhood has recently been creatively used to extend to something very interesting over the past few years. A collection of artists, poets, lawyers and priests, have been able to slowly move that dial in a different direction from the one that moves money to politics. A pendulum swing to counter Corporate Personhood.

Anthropology is the study of humanness and ways of being. It is understanding language and ideas and how those constructs shape the way we define our worlds. I mean this in a very literal sense, that our language can change the way the world is for us. If you can name it, it becomes.

There are languages that have no distinction between blue and green other than a varying shade of the same color. There are languages that have whole philosophies encased in single words, words like Aufheben.

It is a power that fascinates me, the naming of things creates. This happens in the mapping of things, we picture location and relation and present it and it defines a feeling of place, and it can be wrong but that doesn’t change the feeling that has been accepted or believed. To name is to create.

There is a philosophical tool that looks at the divisible oneness of things, that all things can be divided into parts but are also at the same time one. Plato worked on the idea of the one and the many, Aristotle, Hegel; it is at the heart of the idea and concept of the holy trinity and the oneness of God. Our body is a great example of this, it has organs and structures, things that can be taken and looked at separately, systems that are independent, but part of the whole. A community can be looked at as a similar structure, a village, a city, a county, a town. There are biological systems that capture this as well; mycelium, the mass of branched, tubular filaments of fungi that send electric pulses through the underground to communicate not just with each other but from one plant to another. It is a oneness of the forest and a divisible group of parts. A coral reef. This planet Earth. All of these can be looked at differently and expressed differently through the language we use to describe, it is a magic we humans have, but also a limitation.

In February 2021, Mutehekau Shipu achieved legal personhood and shifted language and ideas. Mutehekau Shipu is also known as the Magpie River and is in Quebec Canada. It is not the first of it’s kind ( the Whanganui River in New Zealand was the first designated river with personhood in 2017) but the first in North America. From its sacred headwaters to the Gulf of St Lawrence, it is a whole, an environmental system, an ecosystem. It is recognized by the federal Government of Canada as a person with rights.Some of those rights being:

The right to live, to exist and to flow.

The right to the respect for its natural cycles.

The right to evolve naturally, to be protected and preserved.

The right to maintain its natural biodiversity.

The right to perform its essential functions within its ecosystem.

The right to maintain its integrity.

The right to be free from pollution.

The right to regenerate and be restored.

The right to sue.

To name is to create.

In Ecuador (a place that changed its constitution to allow for the Rights of Nature) there is a rainforest called Los Cedros which is a particular ecosystem. In this forest a handful of musicians and poets gathered to compose a song called Song of the Cedars. This forest, with the rights of legal personhood, could be allowed to be credited as one of the composers of this song, a commodity which is sold and paid for with each click of the computer. Royalties are due to the composers and artists, and the legal framework, this kind of framework, allows for some very interesting avenues for conservation and philanthropic funding. To name is to create.

This is a very new way at looking at things, although, not really, it is an ancient way as well; but by using the same fluid defining of things that the legal mechanisms associated with corporate personhood and property have, you can imagine what might be possible with the realization and remembering that ecosystems are bodies in and of themselves, that a river system is a whole, a coral reef a large living being, a forest a body. What wonderful capacity for hope we can have knowing these tools once used to destroy can also be used to create.

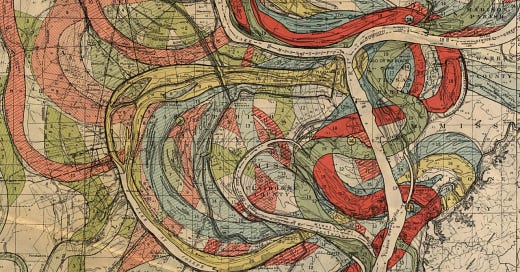

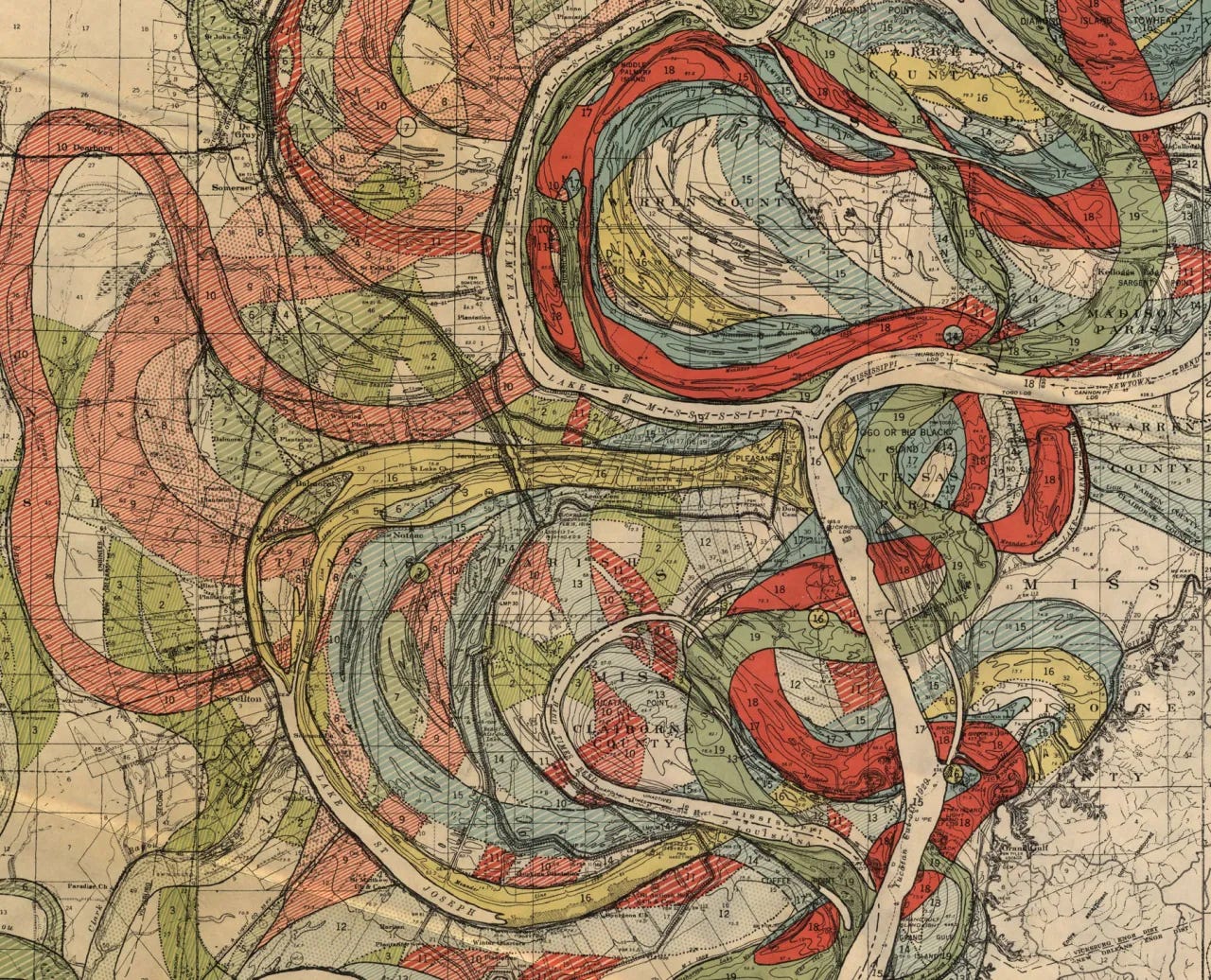

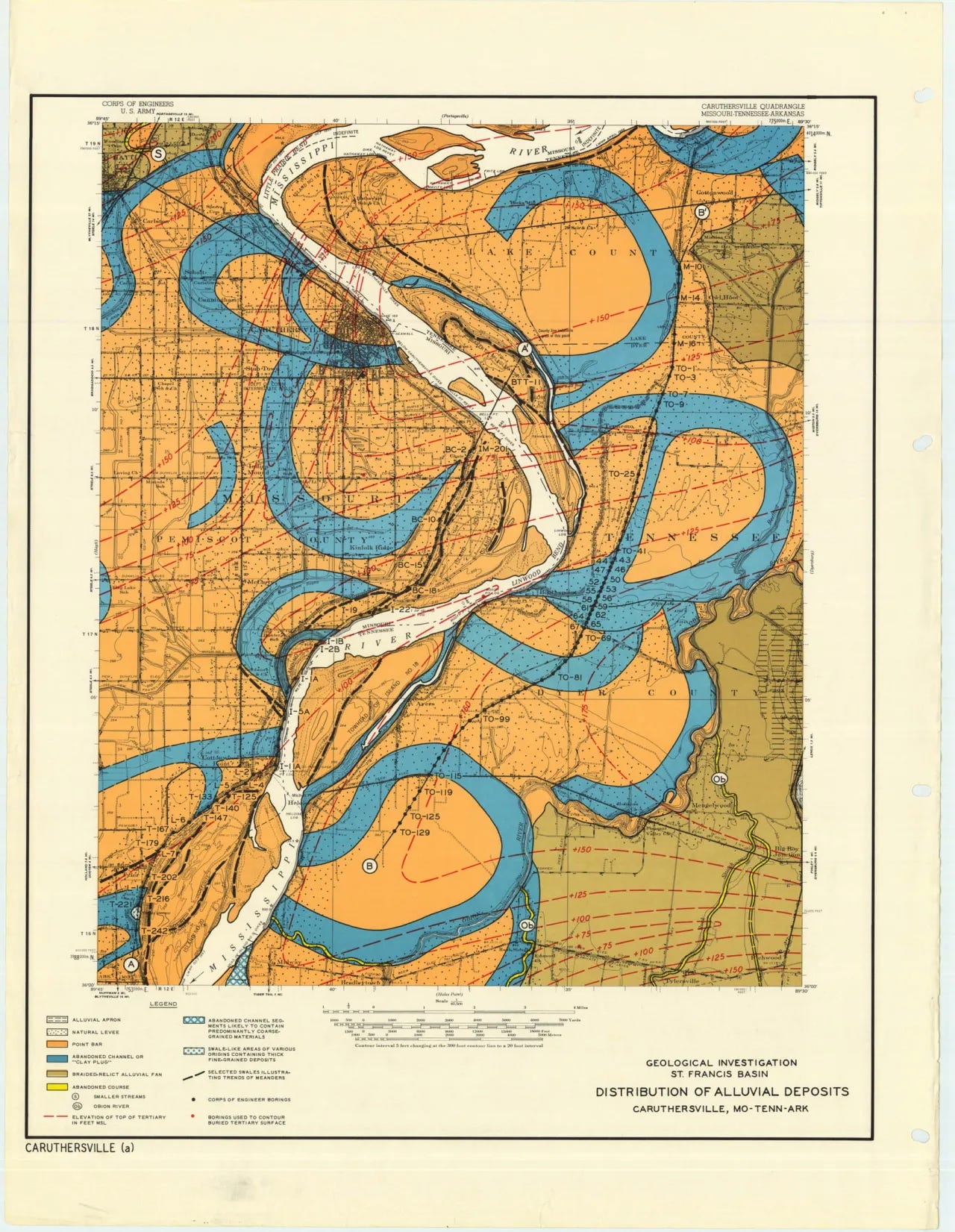

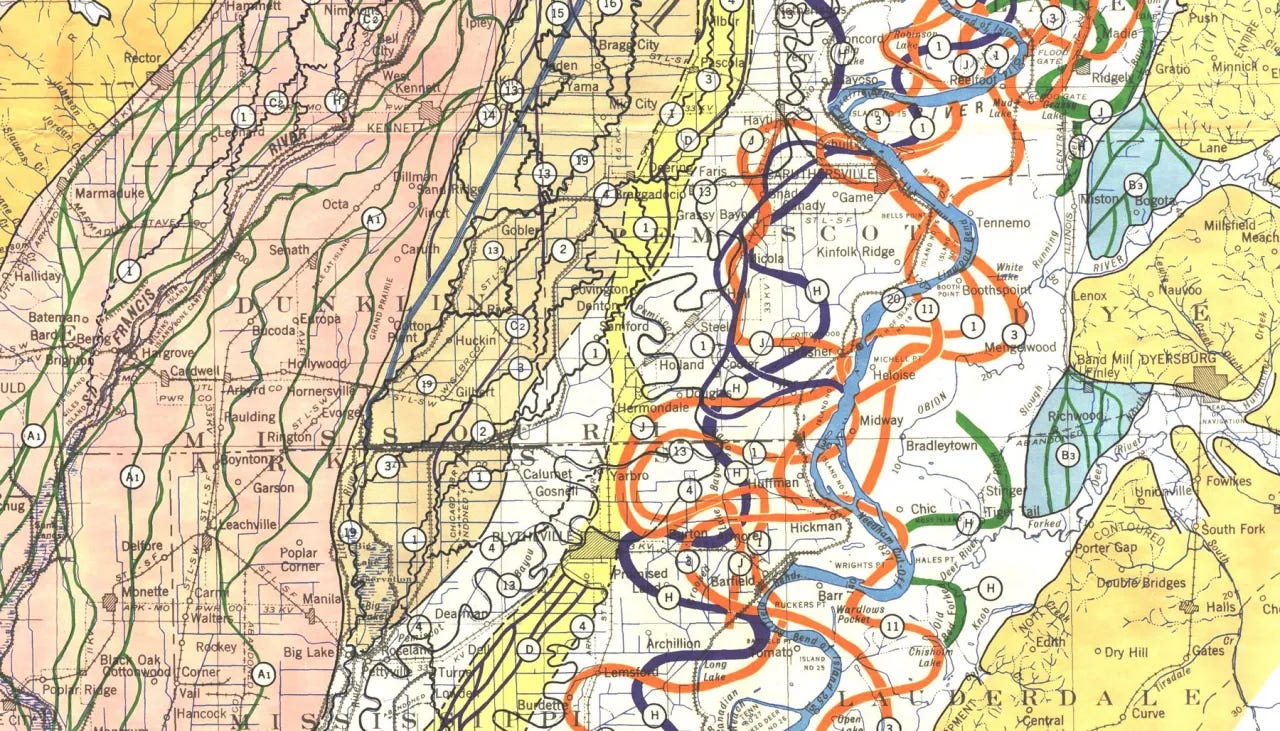

The Orkhon River in Mongolia is a place I return to every few years and am drawn to it like a pilgrim. Each time I see it, it has changed. It meanders as a river should. It moves and flows and whips and curls. It leaves eddies and ponds in its motion. It slowly eats the floor of the steppe away and carves out a valley deeper and deeper each year. I love its wildness, its unbounded self. It will change from one day to the next, breaching a bank here or there. To see a river like this you can feel its oneness, you can name it. There are maps of the historical motion of the Mississippi or the Mekong that show the same, tracing time and motion of this system of life. The maps are beautiful and there is something familiar in the patterns, something lived through that I can relate to. Just as we are constantly shedding skin and changing, ageing and in motion, never the same person twice, rivers represent this and relate to this, they are indeterminate. It is what Heraclitus was talking about when he said you can’t step in the same river twice, that the river is different, and so are you. It is the connecting idea of life and motion and change.

I am still geographically confused, not fully of political bodies or boundaries, but in many ways I feel much more akin to an ecosystem than a nation. I feel a part of my community because we live and move and function together as a whole, and I feel this in the rivers I walk and bike along to get to work, the lake I live near, the weather patterns I experience, the circadian rhythms of place and time constantly in flux, all together.