the magnetic fields

Lessons on slow time and birds, Margaret Atwood, Graeme Gibson, and Pelee Island, and the strange qualities of borderlands and quantum physics.

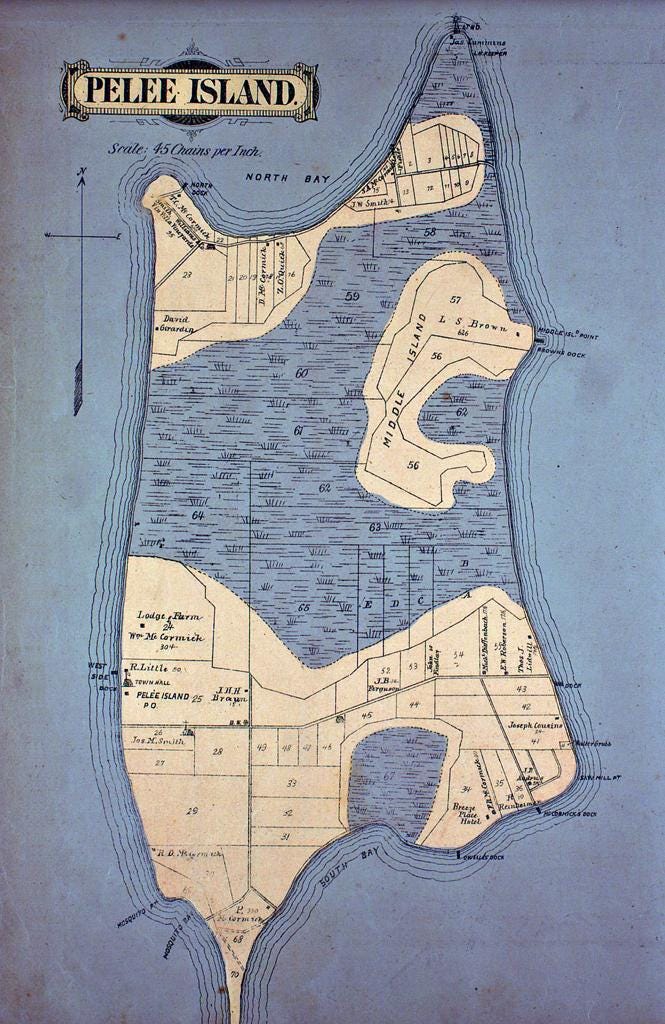

A few weeks ago, with a handful of other curious minds, I packed a bag and fled the city of Toronto to head South West, to the most southern tip of geopolitical Canada, a small limestone island in the middle of a great lake. The island is known because of its geology and geography. Geographically because it is a border, a line between two places. It once was a small hill in a flat dry zone 12,000 years ago, and as the water slowly filled, Lake Erie was formed. The island, whose name is derived from the French word meaning bare, is an hour and a half ferry ride from the mainland to the north. Because of all of this, proximity and location, it is in the path of two major migratory flyways for songbirds that winter in Central and South America and breed in Ontario. In the Spring and the Fall the motion begins. This was mid September. We were there to observe birds.

During the time of covid, like many others, I started to notice things. I had the economy of time at my disposal, things slowed, and I began to notice natural patterns and paces rather than being occupied by day to day tasks and computer screens and apps, there were hours idle, watching, waiting. I had felt this before and knew how to enter this particular temple.

In the early 2000’s I took a semester off of studies from University (in part was asked to by my department due to lack of focus and grades, some would call it academic probation, I called it a recalibration as I am one for self-defining). I took a semester off and moved into a 10x10 foot prospectors tent in North Georgia (state not country) at a summer camp I had worked with the previous summer. There were two of us in late March, my friend Daniel, and two tents. We both studied philosophy, specifically Aristotle, so we were the perfect petri dish for this sort of thing. We lived in those tents for 6 months and watched the seasons shift and the light change. We felt circadian rhythms. I would sit in my tent with the walls rolled up as to have a breeze and deer would roam past, and wild turkey. The plants sprouted and the cacophony of a forest alive would wake me every morning.

The North American shutdowns began in a similar season, March, early spring.

All of this was in my tool belt as covid locked us all in; philosophy and rhythms. In North Georgia I had noticed the plants more than anything else. There were skunk and squirrel, and that wonderfully strange creature, the opossum, but I never noticed the birds. With Covid I was in the city, and the deer and turkey were sparse, so the birds shined, and as the first few robins began to fly through southern Ontario, we all noticed.

Now, I am become birder.

To get to Pelee island, one can catch a ferry from the village of Kingsville or Leamington. We were set for the later. An agricultural town, home to the largest concentration of greenhouses in North America with nearly 2000 acres “under cover”. This coverage is thanks, in part, to Henry J. Heinz and the industry of turning tomatoes into ketchup. Heinz Ketchup production moved into town in 1908, and abruptly left in 2013 after Warren Buffet purchased the company and decided to cut costs. French’s condiments swooped in and kept the production line moving. The legalization of Cannabis also adds to the greenhouse cover. A strange landscape for a bird to fly over; false sunlight trapped in mile long glass houses. The effects of the size and lighting structures creates an omni-present false sunset effect for metro Detroit 30 miles North-West from here. The migratory patterns of agricultural work mirroring the bird patterns, with Leamington needing seasonal swells of human hands to work the earth, housing 10% of its population from Latin America.

From Leamington it is an hour and a half ferry ride to the south before you land on the shore of Pelee, over the shallow waters of Lake Erie. The correct amount of time to set a pace, to slow things down, and with the drone of an engine sound from the ferry, it sets one into a watery dream state heading toward a dotted line on the map that signifies the end of one country, and the start of another.

I enjoy the fringes, where things merge and shift and are in a state of flux, a hut at the edge of a village. I lived in China for a number of years and spent a great amount of time in Xinjiang province, a place that is currently no longer. It has been systematically changed into something else. When I was there, the shifting had begun, slowly, but there was vestige in the landscape, and just south of Kashgar I would drive into a middle space, a valley in between the KunLun and Karakoram Mountains, to a place called Tashkurgan; an ancient fortress that marked a boundary. Ptolemy wrote about a stone tower that marks the midpoint of the Silk Road, this was Tashkurgan. The geopolitic of China dissipates from here and Tajikistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and India all converge in a warp weave of disputed lines on top of the mountainous landscape. My pulse would rise.

But birds don’t see geopolitics; they see landscapes, weather, water, and magnetic fields. Pelee is a border in all of these senses, and an island refuge on a long haul over.

Margaret Atwood and Graeme Gibson came here years ago, to watch the birds migrate. They came over and over and over, season after season. They purchased land and built a simple elegant cabin in the wood, and began to set up the Pelee Island Bird Observatory (PIBO), as well as a process to band birds that was not as violent as past collection systems. There have been times, in the name of science, when through the process of collecting and observing nature, the subject being observed has suffered greatly. Early specimens for Museums and birding societies would go through hundreds of specimens until a perfect example was shown, culling many along the way. In bird banding, often birds will spend hours in nets, sometimes licked to death by passing deer. Gibson and crew decided to have a revolving net checking system every 30 minutes cutting down harm on any of the songbirds caught to be banded. Volunteer run, it is a place of heart and soul. I was there with PIBO, participating and watching for the few days, and staying in that simple elegant cabin in the wood.

A place that is defined by what it isn’t. There aren’t many locked doors, and there aren’t large grocery chains, or fast food, or starbucks, or fast internet, or furniture stores. There aren’t opera houses or highways. Because of these things not here, it opens up space for so much more. We live in a time of over abundance and waste, of consumption and advertisement. To be in a place that is even just a few levels below the normal vibration of the consumed world is a relief. I think the birds must know this in part, they are affected by electro-magnetic waves and vibrations, we have infused our worlds with millions of little waves and vibrations. It all must amount to something that is felt, and the lack of it on Pelee is both a joy and off putting. Off putting at first because you notice the lack of that when you land and walk off the boat, when the hum of the ferry engines wane, you are left with a silence that is absent of all of that small noise we have grown accustomed to, micro waves as opposed to microwaves. The discomfort is from being out of practice, and for some, this is a prize, a place without. I appreciate stillness, and silence, and boredom, I appreciate peripheral vision and daydreaming. It is hard to daydream these days, with so many pings and grabs for attention, instead our focus is always drawn in, into screens and apps and things, a tunnel vision. Pelee is of a periphery, on the fringe, slightly out of focus, slightly out of this mad world.

I think this must be part of why I am attracted to borders, they are the periphery of constructed place, and because of that are the beginnings of the out of focus. Most of the advertisements and businesses that concentrate in the cities would never invest on the fringe, on a border land. These are places that are porous and strange, a certain kind of cultural wilderness that has been pushed to the corners like sauce that collects at the edge of a pot.

During the covid times I spent a great deal of time at a family cottage on another lake north of Toronto. Days were spent there, and my partner and I created a class schedule to keep the rails on our lives. I had a curriculum for my children and would teach throughout the week, mostly nature and simple machines. What a lever is, the states of matter. The kids were young and the Spring was slow so we would find feathers on the forest floor and try to figure out what they were. I found myself trying to teach my children how to live like Victorian scientists: how to be curious and to explore, to pick up the old maggoty bone off the forest floor, not to fear it or think it gross, but to be curious about it and look at it to learn. I didn’t expect this as a parent. I knew I would preach but I didn’t realize how much of this particular gospel I would cast. In my own youth I was curious enough to pick things up off the floor, but sometimes it was other people’s property that fascinated me, sticky fingers. Once I had a Piano teacher, and sitting in her house one day waiting for my lesson, I saw in a stack next to her fireplace: sepia-tinted rolls covered in Chinese script that I am sure must have been purchased in a market in Beijing on a recent trip. Every week for a month I would sit and stare at these scrolls prior to my lesson, lusting after them for no other reason than their strangeness… until one day I succumbed and took a scroll, quickly shoving it into my backpack.

To be a scientist is a fairly new concept, the word first occurring in the lexicon in 1834, coined by Cambridge professor William Whewell. A couple of hundred years earlier, Francis Bacon changed how we think by conceiving of what was to become modern day science. Bacon shifted the accepted idea from the Aristotelian model of thought experiments, to actually going and seeking out empirical evidence, leaving our dialectic comfort and going out into the world to collect things so we can look at them and learn about them. A philosopher’s want for a library of things. Travel was central in this idea, you had to leave and come back with collected things and contemplate them, write about them; “Many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall increase”. A long driveway that would set off the Enlightenment and end at grand Museums and the plundering of antiquities. The want and need to go out and collect things became a great game for the new world order of the 1800’s. It resulted in such anomalies as the Venus de Milo in the Louvre, and the head of King Ramses II in the front foyer of the British Museum.

When the kids were asleep in this covid cottage time period, I would look through old bookshelves and spend time daydreaming.

One particular evening I found a large red box that looked familiar. The show “The Crown” had been on and we had been watching it, and there were scenes where the Queen would be given a daily red box with the news of the day. This was the same shape and had the same royal seal. It felt hidden and secret and forgotten and surreal. It wasn’t in a special spot, it was under some old wooden classroom rulers and files. But there it was, with a firmness and patina that meant it had to be real. I pulled it out and in the box was a large wax seal and a thick calligraphy style letter signed by King Edward VIII of England presenting a knighthood to a family member of ours. It was the strangeness of the covid times that magnified the dreamstate of this moment, a red box found seen in a fictional show about the royals in a time period that seemed out of a 1980’s sci-fi horror, a pandemic. I asked and dug a bit with family members and found that it was indeed a knighthood given to a great grandfather due to his legal leadership presented in negotiations for drawing the lines of the Boundary Waters for the Great Lakes between the then Crown and the young United States of America; the drawing of the dotted line across the waters of Lake Eire.

Last summer I spent a month in a place with no lines, no roads, no fences, open wild space and wild rivers that meander. The heart of a country that was far from the border. I had never spent much time with purely wild rivers, they move and shapeshift, they explore and roam and curl with each storm up river. (Tangentially, there is a new legal mechanism for treating entire river systems as one whole being, this is not new in legal parlance, it is an old legal structure usually used for corporations, only recently has it been successful for natural systems, check out Robert Mcfarlanes new book “Is a River Alive” as well as the Magpie River in Quebec). This was in the Orkhon Valley in Mongolia on a river of the same name, in the steppe and rolling grasslands. I was celebrating the anniversary of a place called the Genghis Khan Retreat. It has had a number of names through the years but what it is really is a summer place to gather. It is also an amazingly significant historical valley, the place that was the capital of Genghis Khan's Kingdom, the origin of the Turkish language and culture, the home of Uyghur history, and strange deep roots to Celtic history I will dive into some other time (there is a wonderful book “The Lost Pianos of Siberia” that talks of this place as well, worthy of a deep dive). At this anniversary were people who had loved the place, myself included. On the first night of this midsummer gathering on the steppe, in a very large Ger (also known as a yurt) a woman in the back yelled out in the middle of a toast “I need some fucking wine!” and I knew then I needed to meet her. She studied Physics and Philosophy at MIT and did postgraduate work in Philosophy, Religion & Psychology at Harvard. She was a visiting Professor at Tsinghua University School of Economics and Management, Beijing, the China Art Academy in Hangzhou, and an Entrepreneurial Mentor at Haier, China. She was included in the 2002 Financial Times Prentice Hall book Business Minds as one of "the world's 50 greatest management thinkers" and her name is Danah Zohar. Danah studied Quantum Mechanics and understands the foundational cultural value of physics in everyday life. That physics is a study of nature, and that these ideas can change the way we relate to our natural world. She understands that Newtonian physics created a modus operandi for a large chunk of the globe to run with, that ideas create movements. From Newton came the industrial revolution, the 40 hour work week, Taylorism, western medicine, Ford’s model T, bureaucracy, division of labor and the scientific method. She is also a soothsayer for what Quantum Mechanics is bringing too many other worlds outside of Physics, in the same way Newton broke open our collective minds.

Quantum mechanics provides new ways of looking at so many things in our day to day lives. Danah used it as a giant analogy for how to structure large businesses and it has a hell of a track record. She has helped Shell, GE, Haier, Volvo, and many others in how to organize large groups, all through the ideas taught in Quantum theory.

There are many strange rules in this physics, but the ones that stand out to me are the duality of small matter and the effect consciousness has on the physical world. These are related to birds and Pelee, stay with me.

In Quantum physics, very small things like photons (light) and atoms have very strange qualities, they can act like a particle (think very small pebble) and they can also act like a wave (think about the top of a pool). The way it manifests depends, in a way, on if it is observed. It is, in a peculiar way, an answer to the question of “if a tree falls in the woods, and no one is there to hear it, does it make a sound?” In a quantum world, the answer might be no, it makes no sound. The building blocks of matter change if we are conscious of them.

Another strange quality of quantum physics is that very small things like photons and electrons, can be in two places at once, electrons can exist, sometimes in large distances, in two places at the same time as far as we can understand. This is called entanglement or radical pairs, and is defined as “a bizarre, counterintuitive phenomenon that explains how two subatomic particles can be intimately linked to each other even if separated by billions of light-years of space.” Duality in space and time, waves and particles that change when consciousness is involved, all point to a central idea of Quantum thinking, the idea of interconnectedness of all things. An idea that, in a lot of ways, is the opposite of Newtonian divisions.

Back to Pelee. As Quantum thinking spreads, much like Newtonian thinking spread to other fields (think western medicine and biology, anthropology, business management) there are new fields of study such as Quantum Biology which are trying to answer questions still unknown in our physical and natural worlds through the ideas of Quantum thinking. One of those questions relates to migration and how certain animals can move, even after a number of generations, across great distances and in seeming ease, return to the same locations over and over and over again. How do Salmon keep coming back across oceans, or butterflies 6 generations later return to the same valley, or small song birds know where to go and return to Pelee over and over, year after year. From Peter J. Hore & Henrik Mouritsen in April 21, 2022 of the Scientific American:

Migrating birds use celestial cues to navigate, much as sailors of yore used the sun and stars to guide them. But unlike humans, birds also detect the magnetic field generated by Earth’s molten core and use it to determine their position and direction. Despite more than 50 years of research into magnetoreception in birds, scientists have been unable to work out exactly how they use this information to stay on course. Recently we and others have made inroads into this enduring mystery. Our experimental evidence suggests something extraordinary: a bird’s compass relies on subtle, fundamentally quantum effects in short-lived molecular fragments, known as radical pairs, formed photochemically in its eyes. That is, the creatures appear to be able to “see” Earth’s magnetic field lines and use that information to chart a course between their breeding and wintering grounds.

Einstein famously called entanglement "spooky action at a distance," which it is. It is spooky and strange, but perhaps it has something to do with with this pull I feel to certain geographies like Pelee, in a similar way birds feel pulled and directed. Observing particles is unavoidably subjective, the observing of a particle changes it, creates it, it becomes because it is observed, and perhaps this is birding, perhaps either the bird or myself become in the act of observing, an omnipresent connectedness in all, we observe each other and connect but also make us more through interacting. Perhaps it is some subconscious recognition of interconnection we all not only emotionally long for, but physically need to truly become in the same way that a wave only becomes a singular particle if observed, if seen. That we are all wave like and fluid on our own, spread out and thinned, that we only begin to become some particular thing when we are in relation to each other, that it takes going out and interacting and meeting and talking when we really become our full singular physical selves. Maybe this is the magnetic draw we feel for travel? Could it be that without knowing it, we have packaged and sold it without understanding it fully? That to go on a trip has very little to do with bed sheets and butlers, that the laws of a certain physics necessitate us interacting, relating, being conscious of, all of us, each other, together as a whole?