The Greater Adjutant

Epiphanies from nature and travel: wetlands in Cambodia, jungles in Paris, and impulsive art love.

I am finding out that I am a birder, a reluctant birder. I have nothing against birding, I just didn’t think I was a birder, but the older I get, the more I see that I fit the profile, and the more and more I fall into birding. I get excited when I see certain species flying. There have been moments, not often, but growing in frequency, moments when I get so excited at the flight of a bird whilst driving that my control of the vehicle could be questioned.

It makes sense. It is a marvel. Creatures with the gift of flight. It is an amazement worth celebrating. So I fault neither birders nor bird, I am just surprised I didn’t know myself better to see this approaching. The pandemic sped it up perhaps. Migration patterns, I think, we all started to notice in those days, when time morphed and changed, and the larger scale of nature’s clock began to be visible again without the noise of human made schedules; long time. And migration and natural patterns are long time. Dave Brower, the famed conservationist nicknamed the Archdruid, used to give a speech about time being a calendar year, where all time begins Jan 1st, the Dinosaurs enter early December. Humans come into the picture on the evening of Dec 31st. In the last 2 seconds before midnight, we begin the modern industrial era. In those last two seconds we find the explosive growth of the human population, the rise of complex technologies, and what we might call a globalized human culture. The hubris involved in thinking we are the center of all is wonderfully demonstrated in this analogy, 2 seconds in a year against the depth of long time.

Perhaps this is what I see reflected when large birds of prey are flying, why I lose control of my car and point to the bird, obsessed.

It is the large birds as well, the birds of prey, but especially, in some strange way I don’t fully understand, I am drawn to cranes and storks. I feel the same way about Ralph Steadman’s art work, there is some part of me that takes over when I see them, a part of me that I am not in control of.

A few summers ago my wife and two children and I were walking through the woods at a family cottage in northern Ontario. It is the kind of place you arrive through a process, requiring you to drive into a different geography, the Canadian Shield, as the roads get smaller and smaller until they run out and the trip finishes by boat. There is a series of family cottages linked by trails from one to another on the shores of a lake formed by ancient ice that once receded. We go yearly, like pilgrims, for a week or two in the summer, an escape. There is internet now but it is slow. Daily we walk up a large exposed Precambrian rock that loops around to a small beach on the bay of the lake. This particular summer, out walking, we turned a corner and there was a large 5 foot tall creature in the trail. I had never seen an animal like this before, it looked like a skinny Emu and I knew there was a farmer close by who enjoyed exotic animals so thought it might be an escapee from the property. But this bird was wild, comfortable in the landscape; it looked at us and walked away, and I was breath taken. A few minutes later we spotted another two further down the trail. It was one of those days that were electric, the sky a soft blue, clear air, everything seemed in technicolor, it was my partner’s birthday and I told her it was an auspicious day, before we saw the creature.

We continued our walk back to the bay and on our return to the cottage we asked relatives who had spent lifetimes summering here if they knew or had heard of this creature. Then we heard the calls, a guttural purr, cavernous, echoing in the bay from a distance, like a velociraptor in Jurassic Park, strange and foreign and birdlike. Relatives in various cottages all stepped out onto their docks looking to the deep cover of forest and wilderness across the waters, like a scene in some Christopher Nolan movie, awestruck and silent. We discovered that these new animals on the lake were Sandhill Cranes, which had moved in, part of the climate shifts our world is going through due to our own industry. My analogy with velociraptors isn’t too far fetched, since Sandhill Cranes have some of the longest fossil histories of any extant bird, the oldest sandhill crane fossil being 2.5 million years old. 2.5 million years is far off 65 million years (dino age) and way far off the precambrian age of the local rock (4,600 million years ago), but they are old no doubt.

Peter Matthiessen had the same crane itch. So much so he spent years writing books, short stories, and adventures seeking them out; Peter, being one of those characters out there in the ether doing things, an always conservationist. He and his friend George Plimpton started the Paris Review (while Peter was working for the CIA using the review as a cover as the story goes). There is even an international Crane organization. I am not alone.

There are 15 crane species on our planet, 10 of which are endangered.

I have a recurring dream of a jungle, really a memory. A few years ago I was in Cambodia in a stretch of land between Phnom Penh and Sihanoukville, a national park called Kirirom. I was helping a group of rangers patrolling the national park as an anti-poaching unit. It was daylight, when most poachers were gone, but the evidence of them, along with their structures, remained. We were finding huts and tools and burning them or dismantling them. We moved by scooter and on foot through the park.

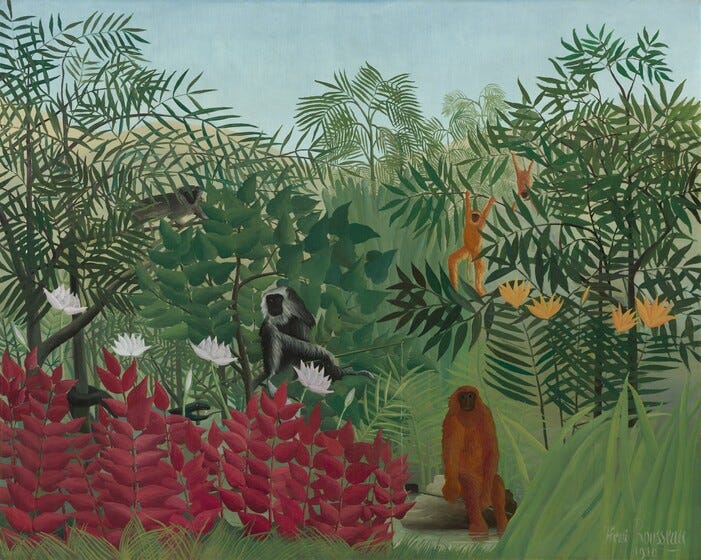

Again, like the sandhill crane in Ontario, we were in a nook of a wood on top of a hill. A place with a small wetland in the middle. An area about the size of a football pitch, like a large amphitheater; a place that had the look of Henri Rousseau’s Jungles in Paris. The men I was with did not speak English nor I Khmer, but we understood what we were there to do. We all stopped when we saw them, fully, we did not breath. There, in the middle of the wetland, were two large creatures. Their eyes were wild, and full, like a goats. Large metallic wedge like bone beaks that stretched 1 foot in length, skeletal. Testicular neck appendages that hang yellow below the head, and 5 foot wing spans at full stretch. They were unhinged from my sense of reality but firmly landed in the natural magic fever dream of real, and they are known as the Greater Adjutant. They, along with the Sandhill, haunt my idea of bird.