Old Irish and Sanskrit

By Manchán Magan. A slice of his new book "Brehons and Brahmins: Resonances between Irish and Indian cultures".

I have a jar of very old yeast (mixed with flour and water) in my kitchen that was given to me by Manchán during one of his wonderful solo touring shows Arán & Im. Manchán wove the Irish language, landscape, poetry, and prose through a couple of hours with ease, all whilst baking a few loaves of sourdough and getting the audience to churn butter. At the end you got to keep some of the sourdough starter to take home and continue. I have had mine for a few years now and my children nicknamed it Bubbles. Manchán’s writing and speech flows like a frothy churn, it bubbles and slowly connects distant parts together. He can bring to life etymology and linguistics. He is one of those special people out there, that when you spend some time with him, your head is spinning with infinities and magic. Below is a chapter from his new book he has kindly allowed us to put out there into the ether. It is on connections between Ireland and India. There are old forgotten histories that show up in the tide marks of language and mythos, Manchán has a way of finding them with ease like some sort of seer.

Ireland and India seem far apart, with apparently little in common in terms of culture, language, and tradition. Yet appearances can be deceiving: there are, in fact, remarkable similarities between the cultures that, once noticed, are impossible to ignore. They point to a shared kinship thousands of years ago that upends the concept of separation between Eastern and Western cultures.

We are both descendants of the Indo-European peoples who migrated west to Europe and south-east to India from a central area between Russia, Ukraine, and western Kazakhstan thousands of years ago. (Some argue that it was from Asia Minor, now Turkey, that they spread, or Armenia, or maybe even India itself.) These early migrants brought their language and beliefs with them, along with their pioneering new methods of farming.

The early Indo-European language they spoke became the basis for almost all European languages. One significant branch of this early language was proto-Celtic, which by the third century BC was spoken from Ireland, in the west, through to the central plain of Turkey, in the east. It morphed into a variety of Celtic languages and cultures that over time were eroded by a slew of invading armies and empires passing through mainland Europe. The Greek and Roman empires were particularly influential in eroding Celtic influence and replacing it with Hellenic and Latin culture through much of Europe, but Ireland managed to avoid these outside influences until Christian missionaries began to appear in the fifth century AD.

Being on the far western margins, Ireland was able to preserve a surprising amount of its early Indo-European culture, and India was able to do likewise on the eastern margins. In Ireland we avoided dilution of the customs, beliefs, and language that had taken root here and so retained aspects of the culture that we had once shared with people on the Indian subcontinent. Think of it as a pebble dropped into a pool that caused circular ripples to radiate out: Ireland and India are like different points on the same ripple.

The linguistic similarities between Irish and Indian languages such as Hindi, Bengali, and Punjabi are accepted by scholars and most likely arose from their common linguistic ancestor, Proto-Indo European. The most widespread hypothesis holds that this early mother language was spoken by farmers living in the Pontic steppe, north of the Black Sea, in the fourth millennium BC. As people spread out, the language evolved into different language families, such as Celtic languages, Indo-Iranian, Hellenic, Balto-Slavic and Germanic. Most European and West Asian languages stem from this same root, but migration patterns and cultural exchanges caused them to adapt and evolve so much since then that it can be hard to see what once united them.

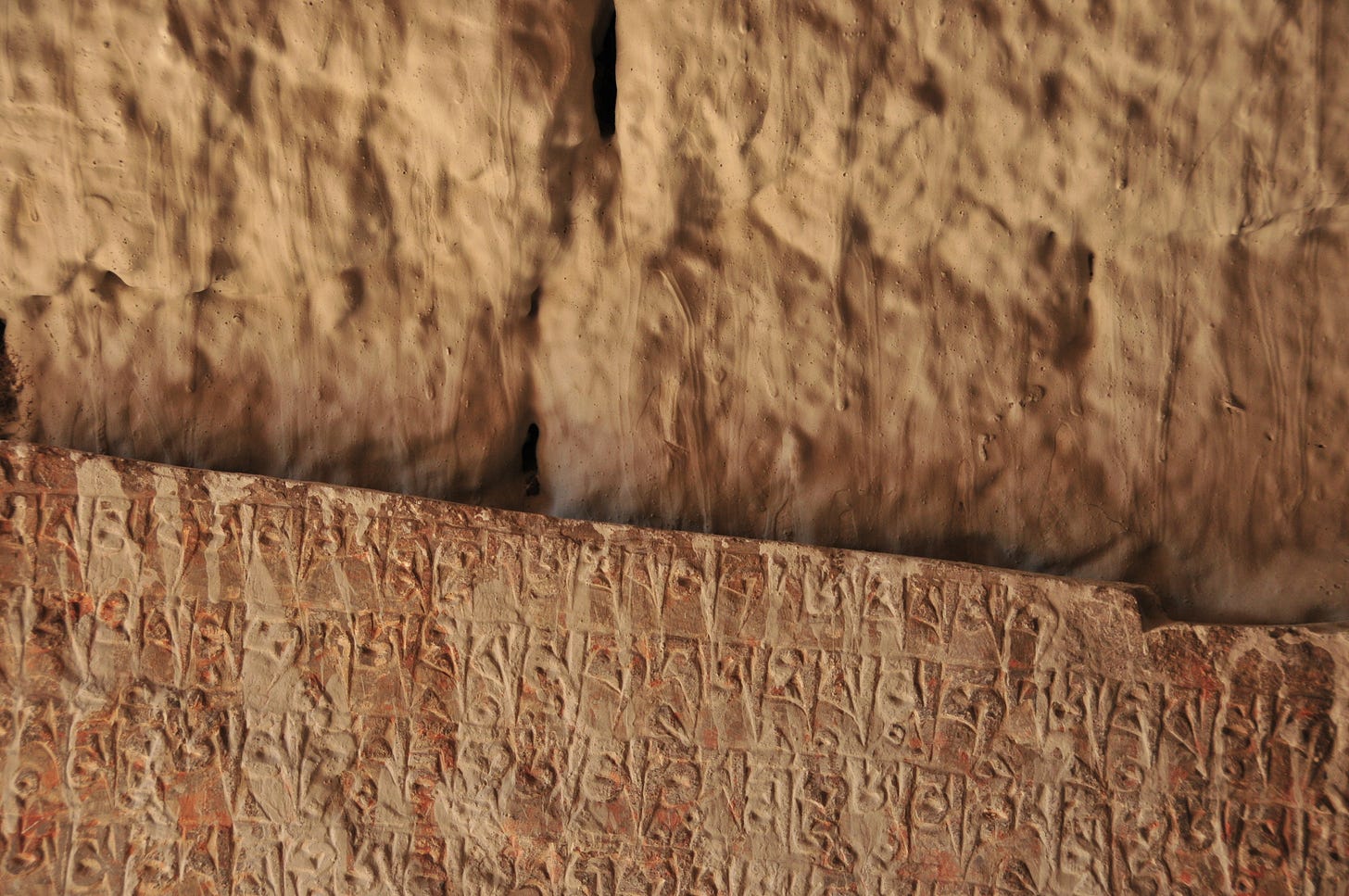

Irish and Sanskrit (and the modern Indian languages that stem from Sanskrit, such as Hindi) have retained a remarkable number of similar words and grammatical constructions, possibly because they were able to conserve old qualities for longer as a result of their history and location. Words that appear to be shared include the Irish word aire (which refers to ‘nobles’, the highest caste in Ireland) and the Sanskrit word aryas (‘noblemen’ in North Indian society), and naib, a Sanskrit word for ‘good’, which is from the same ancestral root as the Old Irish word noeib, from which the modern Irish word naomh (‘saint’) derives.

Other parallel words include the Sanskrit badhira (‘deaf’), which is bodhar in Irish, and the Sanskrit udaka (‘water’), which is uisce in Irish. The Sanskrit trasa (‘to cross’) is trasna in Irish. Āhāra (‘to eat’) is itheadh in Irish. Balacha (‘boy’ in Bengali and Hindi) is buachail in Irish. Even the present tense of the copula (a word that connects the subject and predicate in a sentence) is remarkably similar in both languages: In Irish it is conjugated as Is mé, is tú, is é / is í, is sinn, is sibh, and s’iad, and in Sanskrit it is Asmi, Asi, Asti, Smah, Stha, and Santi.

There are many other features that show remarkable commonality, such as aspiration, in which consonants are occasionally pronounced with an accompanying forceful expulsion of air, and nasalization, whereby a sound is pronounced by allowing air to escape through the nose at the same time as it flows through the mouth. In fact, Prof. Calvert Watkins of Harvard University believed that the structure of Old Irish (the version of the languages spoken in Ireland from the seventh to the tenth century and that is still somewhat comprehensible to Irish speakers today) is most closely related to Vedic Sanskrit.

These linguistic connections are certainly not clearcut, but they do serve to remind us of the intricate web of human interaction and exchange. They are a testament to the enduring quest for communication, expression, and the preservation of ideas, transcending time and borders.

Brehons and Brahmins: Resonances between Irish and Indian Cultures by Manchán Magan is published and can be purchased through mayobooks.ie. He also is the author of the award-winning, best-selling Thirty-Two Words for Field (Gill, 2000), and Listen to the Land Speak (Gill, 2022). He has had TV shows, documentary films, radio shows, he is on the move and his mind is a hive of electrons. You should check out his 7 part series on John Moriarty.

Aurélie Beatley is an illustrator and animator based in Scotland who specializes in folklore, mythology, and endangered languages. www.aureliebeatley.com