It’s impossible to say when winter ended. I was probably sick back then, already. My digestion was uncooperative. However, I was lean and strong. I’d been sleeping well, more or less. A few nights had been interrupted by waking up in a cold sweat. Then suddenly, someone was giving me a hard time. Work was similar: nothing but arguments. I had a fight about money. What a long and drawn out headache it all was. “Enough of that!” I thought to myself. I decided to take a trip around the world, both to face things and to get away from it all: arguments about money and headaches.

I flew to British Colombia. Beautiful mountains, ocean air and lifestyle. My friend there takes a jet ski to work. He commutes from some island to downtown Vancouver. He surfs and skis on the same day. My other friend owns real estate and also skis. Nice lifestyle they have.

I flew to Tokyo. My friend there drives a taxi. He showed me everything. Tokyo… we cruised in his taxi for a day. I’ve basically seen it all. Somethings I showed myself. Sumida City and the Hokusai Museum; Shinagawa, Todoroki Gorge which is a beautiful green scar running through the side of one of Tokyo’s cities. In another part of Tokyo there’s a museum for salt and tobacco—two of my favourite things. I ate several times a day: two lunches and two dinners. A conspiracy of restaurants. My taxi driving friend took me to a master who offered me fugu—dangerous fish—but told me I had to come back in October when it was in season. It was his last year as a master: 49 years since he first cut the fugu. “No poison. No poison.” He was retiring. I don’t think I’ll make it for fugu season this autumn. Instead, he cooked us steak, sashimi, buckwheat ramen while a local drunk, Mr. Tanabe, offered me a tsunami of Ballentine’s then Chivas. Tanabe kept screaming “Highball” over and over.

I flew to Taipei. I have no friend there but I used to live in the Jingan Market area when I was 15 years younger. Met my wife there. Lived the happiest days of my life there. Was free there. Learned that I could live, really live there. I remember one day swimming in the sea off the coast by Keelung and I’d cut my knee on a rock. And we—the woman I married—kissed me on the mouth while we sank and floated under the sun and wrapped ourselves in polluted but pleasant salty water. After that, the life we went on to live was somewhere else. I forgot, then I remembered. Later, an old man with a mouth full of betelnut recognized me at a restaurant across from my old apartment. He said that I’d grown a beard! I hadn’t eaten at his restaurant in fifteen years. That was a long time ago in my memory but perhaps not for him. Perhaps betelnut sharpens recollection? I had forgotten almost everything. Home has been a weak concept for me for a while. And Taipei’s not a place for me anymore. I’ve moved on. I don’t belong there. That’s just memory and there’s nothing to salvage. You see, home is a slippery concept. When you travel, when you go here and there and live and fall in love, you gamble home. Isn’t that a crazy thing to gamble on? And yet, you do it every time you take an airplane.

I went to Seoul to see an old friend. He has a wife and kids. A little house on the edge of a city park. Seoul is one of the best cities humanity has ever created. He’s dynamite too. We drank and ate for a few days. “Rice wine” at a hole in the wall and I was slapped down for not calling it “makgeolli.” A friendly man told me in understanding terms that my vernacular was orientalist—I’d only been in the country for 12 hours before I upended the whole thing with a bit of colonialism. My friend understood it all. He’s at home in Seoul, not in Canada. That’s where we came from. He’s not going back. He can’t imagine it because he’s more at home in Seoul than anywhere. So home is Seoul for him. And his children. Beautiful. Speaking Korean. He gambled and won. Put his home on the line, Nova Scotia, and the dealer pushed back a pile of chips: at home in Seoul with wife, children, makgeolli, and house on the edge of a city park. Enough of that. I’m envious. I’d rather not write about it anymore.

I flew to Tashkent. That’s right! Tash-fucking-kent. Tiki-tiki-tiki-Tashkent! The bazaars there are excellent. I sat next to a girl on the flight from Petersburg. I asked her to remind me of the names of fruits and drinks in Russian, to refresh my memory. The evening of the day I landed I ran into her at a bazaar. That same girl from Petersburg! I had plastic sacks of raspberries, mulberries, apricots, raisins and all types of nuts. She gave me fresh cucumbers. We ate these things on the street, under a tree, we washed them in bottled water. You see, Uzbekistan in very hot. Cold bottled water and fresh fruit under a tree in Tashkent, also, girl from Petersburg: this is a perfect late afternoon for oddballs. Such a long way from home—whatever that is—and yet it felt like something I had wanted to do my entire life. I speak a bit of Russian: please and thank you, names of fruits and nuts. I’m better at Polish and people kept asking me if I was from Czech or Ukraine. You see I mix in Polish to fill out my bad Russian. Anyways, I think I got a parasite from not washing the fruit well enough. I’ve got a thing called blastocystis hominis living in my intestine. It’s not the first time an experience with a girl from Peterburg has left me with “something.”

Before the parasite ruined my health, I left Tashkent and went to the border with Tajikistan. My driver, Sasha Petrovic, talked with me in Russian the whole time. What a bore that was for him and what a pain in the balls for me! Then he asked me: “What do you think of Muslims?” Great question! That’s Sasha Petrovic for you, always cutting to the heart of the matter. “I have lots of Muslim friends in Canada. They’re from all over: Saudi, Iran, Azerbaijan, Morocco, Lebanon, everywhere.” He got the point. I’m ecumenical. There was no need for him to worry about me. I should have asked him, “What do you think of non-believers?” But I didn’t care. You see, that seems to be the difference between them and us. Sasha Petrovic yelled at his phone several times when the navigation or the translation function was too slow. He screamed, “Fuck your mother!” at the phone. That’s basic Russian and it sounds like yob tvoyo mat. At such moments we understood each other best. I wonder what he would’ve yelled if I’d said I didn’t like Muslims?

We spent a few days in the Tian Shan mountains. The “Uzbek Switzerland.” I’ve never understood the tendency to do this to unfamiliar locations. Why can’t the Alps be the Uzbek peaks of Europe? On a mountain side, Ms. Tatiana, a stranger, asked me what I was doing there. I said, eventually, I’m going to Nukus. She looked at me with a faraway charmed gaze and said, “Savitsky.” That’s the name of a special museum. Later she helped me hitchhike off the mountain side to the parking lot where Sasha Petrovic was waiting, napping in his Chevrolet.

In the Spring, the mountain slopes and valleys East of Tashkent are abundant with green. I told Sasha Petrovic that the view was beautiful. He said that the colour was better a month before. There was a lament in his voice. He has a special affinity for the mountains when they’re at their greenest but the water was already going away and there was little rain to replenish: the colour green was fading. He didn’t swear at the fading of green the way he cursed at his smartphone when the navigation frustrated him. But maybe he should’ve. Water scarcity changes the landscape in the mountains but the damage is limited by the presence of a managed reservoir, Lake Charvak. As you travel westward in Uzbekistan—one of the world’s only double landlocked countries—the drying of the land accelerates to the extreme degree. On the dry side of Uzbekistan, water is a memory.

After a few days of exploring eastern Uzbekistan with its cool mountain air, fresh colourful countryside vistas and friendly Tajik merchants selling fake Ray Ban sunglasses, Sasha Petrovic drove me to the Islam Karimov Airport and I flew to Karakalpakstan. I gave Sasha Petrovic about a month worth of typical salary for his trouble (half in Uzbek Sum and half in Euros) and said goodbye forever. Now that I think about it, I’m certain his name wasn’t Sasha Petrovic. It was something more Turkic or Uzbek. Never mind, all Russian speaking men are Sasha Petrovics to me until I learn their actual names. I hope that this Sasha Petrovic is well and that he had a good time with the money I gave him but I’ll never know. He took really good care of me, drove me around and watched my back while I was off the grid. I’ll never forget him. Also, the way he screamed “Fuck your mother” at his smartphone! When it comes to technology, there’s a little Sasha Petrovic in all of us!

I landed in Nukus. I had no guide there, no Sasha Petrovic to drive me around. I tried to use my feet. But I hadn’t accounted for the forty degrees of Celsius around me. Nevermind! I knew something interesting was in the area. One year prior, a friend—someone who knows about this sort of thing—promised me interesting things in Nukus while we were at a public house in Toronto.

The air was dry and tasted of salt and dust. The colours of the eastern mountains were replaced by a stone and sand palate. Chromatically, it reminded me of images of Mesopotamia. I was on the banks of the Amur Darya, half a day drive to the Aral Sea. Somewhere in Nukus was a museum of great significance: place of pilgrimage for oddballs such as me: that same museum called Savitsky of Ms. Tatiana’s faraway gaze.

The city was sleepy because of the intense heat. I’d arrived in the late morning. The Karakalpaks were wisely staying in the shade. Karakalpaks are not Uzbeks… I later learned. They are less likely to speak Russian and less likely to be out and about during a scorching midday inferno.

In the hellish climate surrounding the remnants of the Aral Sea there are occasional blizzards of salt. One of these storms ravaged the area’s agriculture in 2018. A local said, “Nature has begun to take revenge on us for what we did to the Aral Sea.” The Aral Sea was starved of its source water by Soviet bungling. Soviets ruined the Aral Sea and now it’s a wasteland of salt and dust. But Nukus has all the makings of a fine city. There is a large bazaar, a shopping plaza that reminded me of a Shanghai emporium, and, of course, there was the museum. I found it after an hour of walking under an unforgiving sun. It emerged like a mountain over a flat plain.

The museum is named for it’s first curator, Savitsky. It houses Russian avante-garde paintings in styles banned by Stalin in the 30s—Russians did to culture the same thing they did to water. They left the people with dust. The museum is an oasis of rescued artworks and is called the Louvre of Uzbekistan—as I told you, I don’t approve of this stylization, I think, the Louvre could be the Savitsky Museum of France! But it’s an oasis all the same. There are only idiomatic reasons for this beautiful contingency in that ominously dry region in the far West of Uzbekistan. The Savitsky collection crosses several periods in Russian avant-garde painting. I spent several hours there. I had three experiences which gave me pause. The first was an overwhelming reaction to a painting by V.I. Prager (1903-1960): an oil painting of “Polya.” The woman in the portrait, Polya, had a striking resemblance to my estranged wife just at the time we met in our mid 20s. It even recalled her haircut and the fierceness of her Slavic perturbation when she glanced pensively. Reminded me of our fiercest arguments from that innocent time, “Did you eat my banana?” she scolded me one morning before work, “From now on we’re buying our own separate fruits!” Then she looked at me like this!

The second was an exhibit titled the “memory of water” which recalled, in paintings, the Aral Sea. These things attracted me with their pathos: images of lost homes. My once and vanished home was insinuated in the portrait of Polya. And someone else’s once and vanished home was caught in the memory of water. Of all the beautiful things that have died very few are accessible, but where they are accessible, it often happens to be in museums.

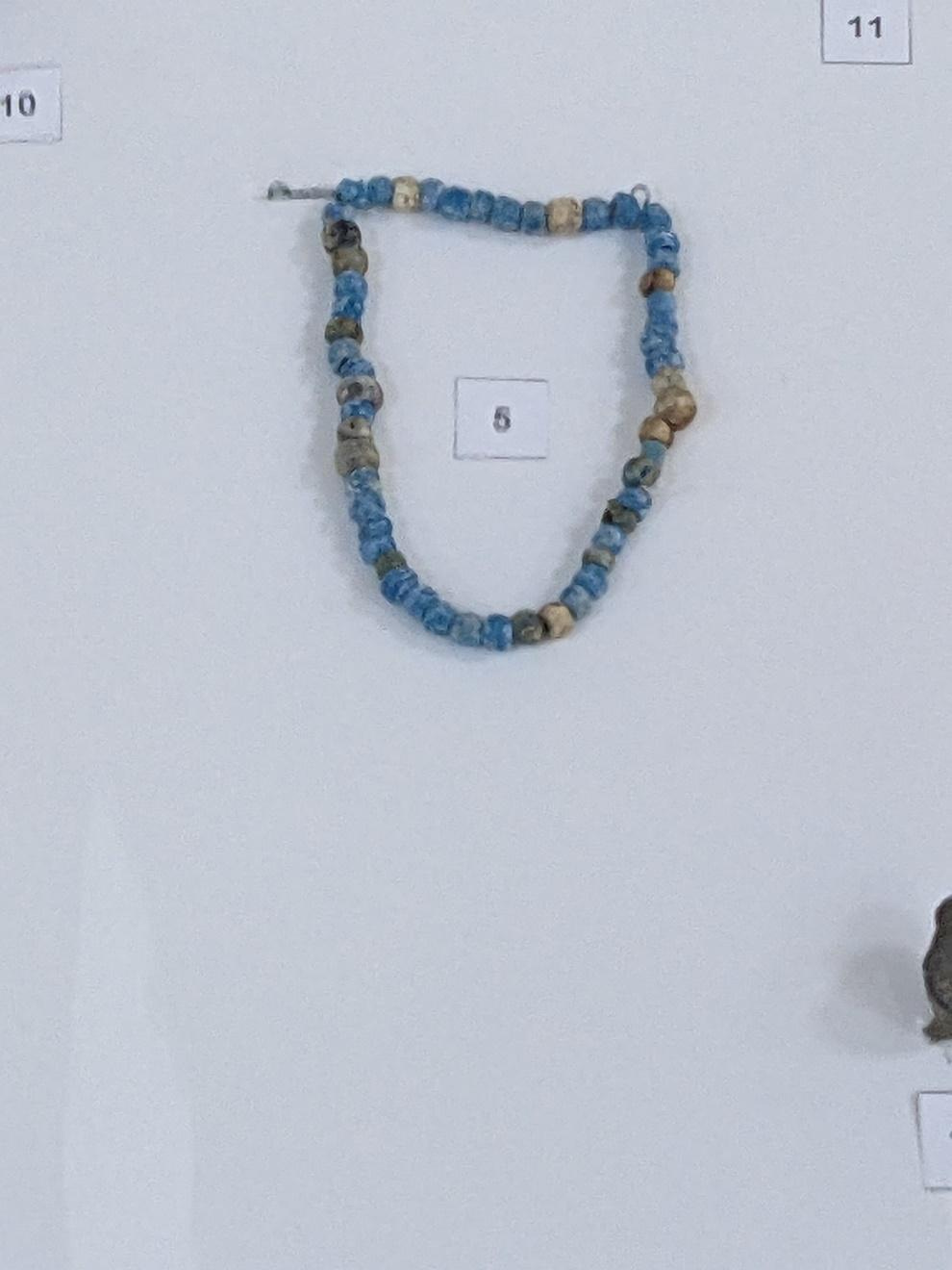

A third thing seemed even more fortuitous. I was wearing a blue and gold bracelet which was a gift from a child in Toronto, little Mia. This youngster was worried I’d be lonely on my trip so she gave it to me to remind me of home. In the Karakalpak anthropological collection, I found a near perfect copy of the bracelet I was wearing. Astonishing but true. Little Mia lamented later that the Karakalpaks had stolen her design! Suddenly, the bracelet worked its magic and I thought of home and my tiny friend. I didn’t feel so lonely.

My tears dried quickly in the heat which had risen substantially when I left the museum. I was thirsty. After a few blocks on foot, a group of men in the shade of a building invited me to sit with them at on plastic chairs around a table. They filled me with cheap beer, cigarettes and questions. How old? Wife? Kids? Job?

Did I have a job? I said I didn’t want to work, “работать не хотел.” I learned this turn of phrase from a song. They laughed and I bought myself their approval. It was evident that they too currently lacked employment so we had that in common. They told me who they were: Karakalpaks! What they were: strong! What they were ready for: war! I had made myself in the company of aspiring insurgents. They were generous with their beer and cigarettes. They also offered me a powdered intoxicant which some of them insisted I take and some of them insisted I not take. I didn’t take. Normally I accept all powders offered to me by strangers but that day I thought, no, it’s too hot. These men, however, remained hospitable. They took their time to air their resentments. They were resentful of something that was all around us, something about the dust and salt. They talked about strength and guns and violence. They asked me which countries I liked and they told me which countries they liked. They liked the countries that were strong and violent because that’s what they wanted to be. This is what happens when the water is gone. Young men become old men interested in strength and violence. What they retained was their tender sense of home. They admonished me with intimations of violence. This was their home. Not Uzbek, not Russia, not Soviet… Karakalpak! After they’d made their point a few hundred times, we laughed about unemployment a bit more and I drank until my thirst was gone.

One of these men had a row of gold teeth instead of the conventional enamel kind. We got along well. I traded him my baseball cap for his skullcap. There’s a golden toothed insurgent in Karakalpakstan wearing a hat promoting the Shore Club in Hubbard’s, Nova Scotia.

After they had talked about violence, strength and unemployment to the point of exhaustion, I excused myself from their company forever. Before I left, they said, “Simon. Karakalpak. Friendship!” We all agreed on this.

I left Nukus on a plane the next day. I felt, what good is this beautiful museum, an oasis of culture, if the idea of home is unsustainable because the water is turned to salt and dust. There is no cure for a lack of water and there is no cure for a destroyed home.

I made my way out of Central Asia to Eastern Europe, first Riga then Warsaw, where I spent time with my estranged family and received medical attention.

A few weeks later I boarded a flight from Warsaw to Toronto. I sat next to a couple who were in their 80s. He was dying. She still had a few good years. She told me, “We will never visit Poland again. Toronto is our home now. This was our last trip.” It was practical, final and unsolicited. As the plane took off, we all looked down on the Vistula and Warsaw. You see, Warsaw is wet and green with a supercharged river. I could make it my home again should I please. One can be at home there.

You should be very careful when you gamble with home. Above all, don’t let your home run out of water. Don’t get on a plane and forget where your home is. You might never make it back. Or you might forget. Or you might remember. Museums are great—if you need a place to cry in the presence of beautiful things—but homes are special.

I’ve been at home struggling to get rid of the parasite that infected me somewhere between Tokyo and Warsaw. But at least I’m home! Here, on the shore of Lake Ontario, I have lots of clean water to drink. From my condo balcony I can see endless vistas of green trees. A view I’m sure Sasha Petrovic would envy.