Moons and Junes and Ferris wheels

George Washington Gale Ferris Jr. grew up in Illinois, obsessed with the moon, its shape, its craters and scarred face. He drew pictures of the moon in grade school and studied it in high school, and when he graduated at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute as a civil engineer, the lunar mark stuck and came back to him in a fever dream when designing a giant Moon-shaped wheel for the World’s Fair in Chicago 1893: the one to celebrate the 400 years since Christopher Columbus landed (himself no stranger of the power of the moon; he once successfully god-feared the people of Jamaica to work for him by predicting a total lunar eclipse in 1504.)

After a few years of living in Asia I remember noticing there were multiple cities I spent time in that had Ferris wheels in prominent places, and most of the time they did not work; stage props to show optimism, sphere shaped, moon-formed masses to be lit up at night and project the image of hope. I had been traveling and living in Asia for over a decade and had seen these monuments on the border with North Korea and China, Yangon, Hanoi, Phnom Penh, Guangzhou, Kashgar. None of them worked.

Most recently it was in Ashgabat, a city in the desert ruled by a mad dictator obsessed with Guinness records, so the Ferris wheel was air conditioned in order to win the claim as the worlds largest indoor Ferris Wheel….but again, non functional. I am convinced that in some user manual for running a dictatorship, there is a clause on having to own a Ferris wheel and plop it in the middle of the city in order to fully rule, that there is some factory in rural Siberia pumping out stage-set-like non-functional Ferris wheels to these cities to keep up the good vibes so the ruling elite can run amok and ride real working Ferris wheels in places like Paris, where they keep a summer apartment in the 6th Arrondissement.

These wheels give a feeling to a population, a feeling of togetherness and the idea of the potential that we all could one day sit there, the dizzy dancing way that you feel spinning on those metal seats above a city; it gives the idea of us and the inspiration birthed from G.W.G. Ferris Jr’s youthful love of the Moon, the O.G. Ferris wheel.

I find myself looking at the Moon a lot this season, and following the Moon cycles to try and wrap my head around tides and how the Moon pulls at all that water around us. I am more superstitious than I would like to admit and feel that the Moon must pull on us, it must have some sort of effect that we are not taking into account. The fact that gravity sends waves and ebbs and flows time and space is known in physics, but I want to hear more about how that keeps me up on full-moon nights, why hospitals fill up and my kids can’t sit still.

The Moon becomes the only celestial body we can study with the naked eye, and thus is the bellwether of “us”. We can all look at the Moon, we can see its face shining back, we can gaze at it unlike with the sun, nor like far off stars that are too small to gather. And this is what I see when I look up, I see us, as one, as whole, as a planet looking up at the same Moon through each of our nights. A moon, like a giant Ferris wheel in the middle of our city.

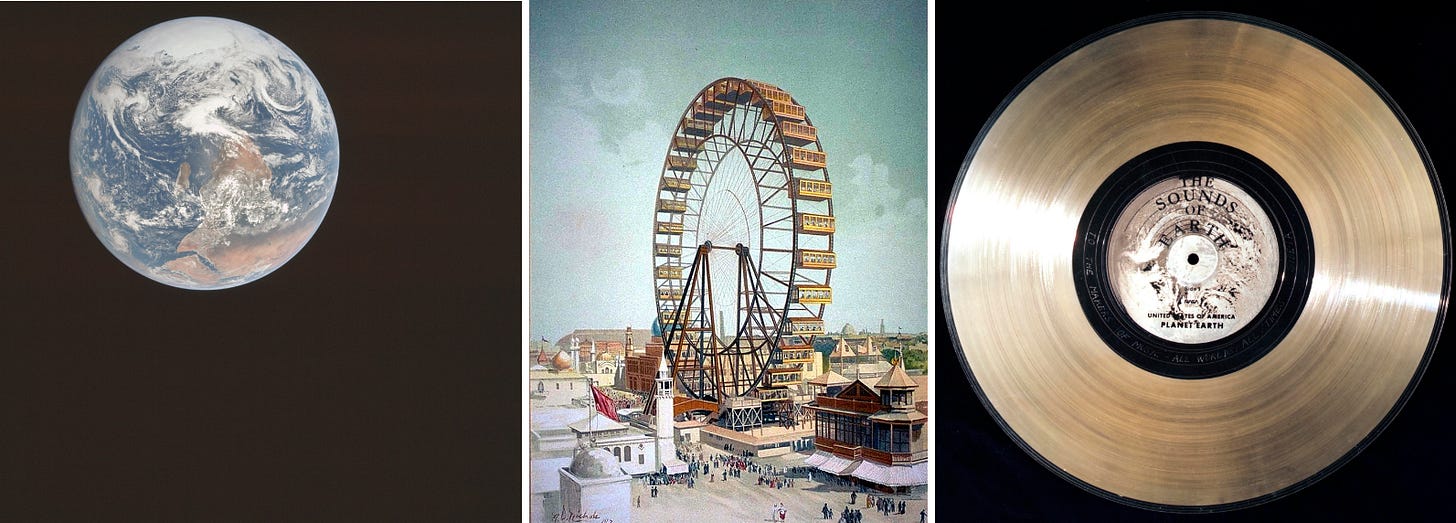

In December of ’68 as well as December of ’72 photos were taken of Earth from the Moon that were the first of their kind. “The Blue Marble”, taken by the crew of Apollo 17 is one of the most reproduced photos of all time, and it should be, it is the visual tidal wave of fact that we are here on one planet, together. It was the first time this particular point of reference needed no fiction, it was stark, and placed us in the empty body of space. It set fire to our collective imaginations and we started, for the first time, to push out past the exosphere. This outward push was a simultaneous inward exploration, seeing a photo of our planet as one, our collective self.

On the heels of “the Blue Marble” photos, in 1977, NASA launched two probes into space, Voyager 1 and 2. Hurtling at 35,000 miles an hour, they are still out there, exploring and sending back photos from the outer limits of what we have seen and known from our pale blue dot Earth. It was decided that it would be a missed opportunity if we were not to represent ourselves in some form or fashion on these moving metal masses. And it would further be a mistake to represent our world only with shop talk. So people sat and thought about what might best show a reduced version of us and our world.

Because music is mathematical and therefore universal, as well as an expression of the emotional human experience, it made the most sense to include songs and sounds of our planet. It also happened to be the 100th year since the invention of the record, so the team in charge of figuring out how to imprint a ghost into the machine called up the head of RCA records to help. Carl Sagan was the head of the group and he called in the help of Alan Lomax, Ann Druyan, Robert Brown, The United Nations, Jimmy Carter, and many others. A copper record was pressed with 90 minutes of music, as well as 117 pictures, greetings in 54 different languages, and hints and clues on who we are and what we do and think.

B.M. Oliver, vice-president for research and development at Hewlett-Packard at the time, summed up a part of the feel by saying “There is only an infinitesimal chance that the plaque will ever be seen by a single extraterrestrial, but it will certainly be seen by billions of terrestrials. Its real function, therefore, is to appeal to and expand the human spirit, and to make contact with extraterrestrial intelligence a welcome expectation of mankind.”

Below-be murmurs of Earth pulled from the greatest mixtape of a time and place. It is an hour of songs from the Voyager and the Golden Record; “a bottle into the cosmic ocean.” This is a radio program I produce for my work with Trufflepig Travel, hence the moniker WPIG the Pig for the radio show. You might notice melancholy in the mix, and that is intentional. Even traveling at 35,000 miles per hour, it will still take them 40,000 years to pass near another star, and long after we are gone, this copper avatar will be preserved, out there, in the ether, with the words written around the run-out “To the makers of music, all worlds, all times.”