There are a few places this boat surfaced for me over the past year or so, enough to make me stop, take notice and wonder.

First, I subscribe to a publication called Archipelago, self described as an occasional magazine (published with no pattern or set dates, just when ready). It is a magazine that has “preoccupations with landscape, with documentary and remembrance, with wilderness and wet, with natural and cultural histories, with language and languages, with the littoral and vestigial, the geological, and topographical, with climates, in terms of both meteorology, ecology and environment; and all these things as metaphor, liminal and subliminal, at the margins, in the unnameable constellation of islands on the Eastern Atlantic coast."

It is niche, yes.

In this magazine there was an essay about an island off of the coast of Ireland and a poet, Richard Murphy, who had lived near there. Richard had restored a boat, an old Galway Hooker. These were handmade wooden sailboats used to move supplies up and down the western coasts and in Galway bay. Richard had restored a boat called the Ave Maria in the 1960’s and wrote about it in his poetry collection Sailing to an Island…and in the essay about this there were photos of the Ave Maria, dry docked, up on blocks in some back garden near the Irish coast in a stage of historical disappearing; not gone but somewhat forgotten, thought to be of the past.

Then, a few months later, I picked up a book by Phillip Marsden called The Summer Isles, where a chapter is dedicated to this same poet and same boat.

It wasn’t the boat alone that stood out.

Richard Murphy had lived a poetic life; youth in Ceylon, boarding school in England, upbringing in western Ireland, and the complicated life of the Anglo-Irish. His poetry was known but under noticed. It was elegant, smooth and curious.

The Ave Maria was special, the last of its kind. The final handmade Galway Hooker finished in 1922 in a Galway neighborhood called the Claddagh. Handcrafted by boatbuilder Sean Cloherty, who died in the act of making the hull. The final nails and planks finished by his daughter; familial blood, tears and sweat. The Claddagh was the west bank of the Corrib river, a part of town that kept old ways longer than the rest of town, outside the Galway walls, horse drawn, hand made, low rise, and up until the early 1970’s, had its own King (a wonder of a man named Martin Oliver). This was the last Galway hooker handmade in the Claddagh. In the early 1900’s there had been over 250 used for transport, fishing and cargo along the fractal coast.

For a number of years the Ave Maria was used to fish in Galway bay, until a priest sailed her for pleasure near a village called Cleggan and an island called Inishbofin (Island of the white cow). The boat had a reputation for bringing good luck to its owners. After that the Ave Maria moved around a few more times before landing in the hands of Richard Murphy.

I wanted to find the Ave Maria, the photos of the boat on blocks stuck and vibrated with me. I dug and found another photo as recent as 2016, with a credit to the photographer named Nic Dunlop. A quick search and I found that Nic is a talented photographer who lives in Bangkok and works in Myanmar often, a place I had lived and worked and was very close to my heart, another chord struck. With the fates at play, I reached out and we set up a time to talk.

In 2007 I moved to Ireland with the intent of living there for at least a year, and to spend my time guiding biking trips and surfing, and possibly living out of a van. The first iphone came out in 2007 so this was no #vanlife trend, and I had spent the past 5 years living in China when it was in the crest of a building boom the world had never seen before. I lusted for wind swept, rural, and quiet. I went, but didn’t end up living the way I thought, instead only spending summers for a number of years, and the rest of the year in Asia and South America. The time I spent in Ireland was mostly in one particular region, the central western coast straight west from Galway City. A place called Connemara.

It is a place defined by sightlines, in that it is deemed Connemara if from where you stand you are able to see the Twelve Bens, or peaks. These peaks are of ancient mountains once connected to the grand Appalachians in the primordial mass of Pangea. If you are too far to see the peaks, then you have ventured outside of Connemara.

Nic had passed through in 2016 when he took the photo, and last saw the boat in person in 2019, he knew the location and sent me the longitude and latitude. It was southern Connemara, stone, harsh, in an Irish speaking region called Cois Fharraige (Beside the Sea). A path was presented.

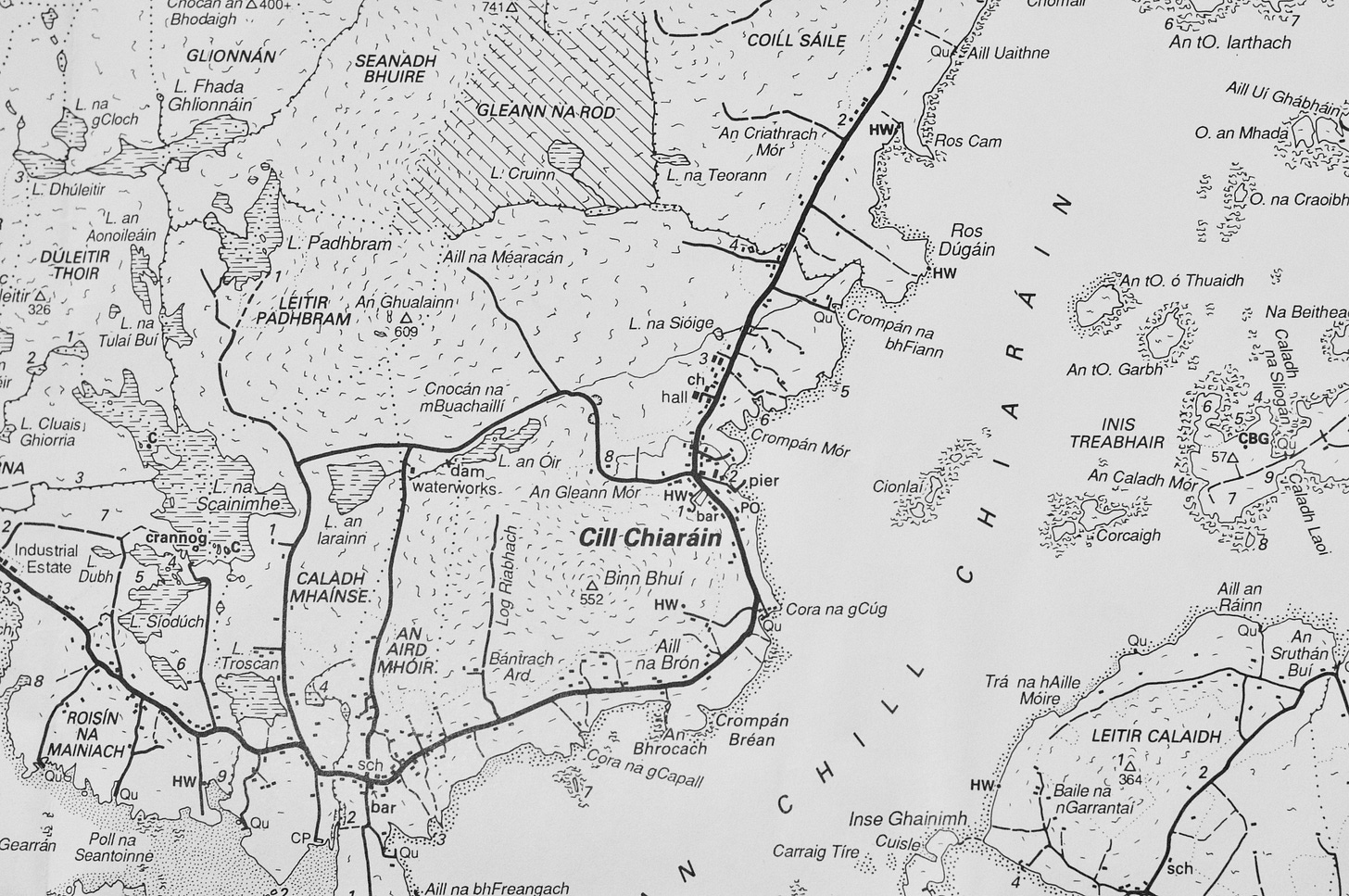

This region interested me. I had spent years in Connemara, on foot or bike, I had explored trails and holy wells. It is not a large landmass on a map, but there are secrets in this folding landscape that hold entire worlds. The distance between Roundstone and Carna is about 7 km by bird, but there are hundreds of kilometers if you follow the coast by foot, through every nook, every bay and inlet, circumnavigating rocky tidal shores. And the kilometers ebb and flow as well, they change daily, they are tidal and move with the pull of the moon. Cois Fharraige exists in this fluctuation, the light shifts with constant weather, the land moves, islands form and sandbanks disappear, it is porous and vibrating, slowly. Names of places move and shift and are intensely locally understood. I am from the southern USA, I have family in Louisiana, I remember after Hurricane Katrina street signs were gone in certain sections of New Orleans, and the knowledge of where things existed was a mixture of hearsay and mythos. This is what Cois Fharraige feels like, to me, but this is because I am not from the landscape. It feels like a dreamt landscape that unfolds as one moves through it, like through fog. This ebb and flow is different closer to the mountain peaks, but the further you get away from the Twelve Bens, and you head south, something starts to change. This is where the Ave Maria was, in a bay known by 5 different names depending on who you asked and when.

I don’t like the modern phone, I am one who thinks the convenience these instruments try and alleviate are not worth the trade offs of privacy and annoyance of advertisements meant to create addictions. But I do use them, and sometimes they can illuminate whole communities in short strokes. I wanted to experiment with social media and put it out there to the various connections to see what 6 degrees of connections I could stir up. I put it out there in the ether that I was looking for this boat and the result was a root system of hidden connections.

A friend wrote and said his grandfather had been the skipper on the Ave Maria. Another wrote that their great uncle had sold the boat to Richard Murphy and was the previous owner. Another two grew up near where the boat was up on blocks and learned to drive stick shift on the tidal beach in the background of the photo. I felt the electricity that comes when you know you are on the right spontaneous track, a rush of blood, a slight tempo in the cadence of my heartbeat. These moments feel delicate, and can be, but this one felt like an old worn path, hard to lose, as if I was somewhat not in control.

It was November. My partner and I packed up our family, purchased the tickets, got on the plane and flew across the pond with some longitude and latitude coordinates in my pocket.

November turns out to be the best kept secret in Ireland weather. There must have been over 50 rainbows, the side light from the horizontal sun makes for watercolor scenes, it was stunning and gorgeous and the winter was yet to set. The summer season businesses are all shut so one must keep that in mind, but it is like being at the actors party after a broadway show, an immediate, can’t-help-but-have honest interaction, the show is over and the real life day to day is omnipresent.

I didn’t want to rush into things and run straight to the x on the map. I wanted to ask around and feel my way through, I wanted to feel the slow pull of the Ave Maria. This is a part that I think is the most delicate in travel, but the most rewarding; leaving things to the unknown, to serendipity and spontaneity. I remember years ago sitting in a board meeting of a travel company where one of the board members asked what the formula was for spontaneity, to which a reply came “it is more like love, or friendship, it feels, and you can only get there by being open”.

If I had wanted to be efficient, I would have gone straight to the Ave Maria to see, but the value, as it often is, is not in the perceived goal, it is in the going to get there, and I wanted to soak as much of that up as I could. I wanted to go slowly and to see where it led. I wanted to be wonderfully inefficient.

A client of mine in Toronto grew up in Ireland, and she had heard what I was looking for and reached out to tell me that her brother was involved in the Galway Hooker Association, a group of people keen on restoring and keeping these particular boats on the water. Not only that but her father had been known as “the Dictionary man” in this part of Ireland, Tomás de Bhaldraithe. He had collected and printed the first definitive Irish-English dictionary in 1959. Tomás had brought his family with him for a number of summers in southern Connemara in order to study lost Irish words still spoken on these fluctuating shores. This is no normal dictionary, with it came political weight, a resurgence of academic study in the Irish language and literature, the start of a long road to rescuing whole landscapes of ideas through a language unknown in origin. Through the Galway Hooker Association I met their commodore, Ciaran Oliver, who’s great uncle was the last King of the Claddagh, Martin Oliver. There is a word, saeculum, that describes the measure of a lifetime linked to an event in the lived history of a place. It means the time from the moment that something happened until the point in time that all people who had lived at the first moment had died. A measurement of a collective lifetime and memory, connective tissues of communities, a memory of a village. This is part of what I wanted to connect with, what I wanted to touch, and I could feel it beginning to happen.

There is something with this particular boat that connects things. The obvious connection of land and water and mainland and island in the pure functionality of a boat, but it connected people as well. Richard Murphy invited friends to sail on the Ave Maria. Famed actor Robert Shaw, the salty captain from the movie Jaws, came and spent time on the coast and on the boat. Poet Theodore Roethke was lured to visit Murphy and sail aboard the Ave Maria, looking for wild power of wind and tide. Roethke stayed out on an island named Inishbofin, where Murphy lived and sailed the Ave Maria for tourists in the summers, and after a few weeks of drink ended up in an asylum on the mainland to dry out, after which he returned right back to the Island and the coast and the Ave Maria.

Sylvia Plath and Ted Hughes came as well “in desperate need of boat and sea” after Sylvia had just finished her novel The Bell Jar. This was the later days of Sylvia’s life and the last few months before she would take her own life.

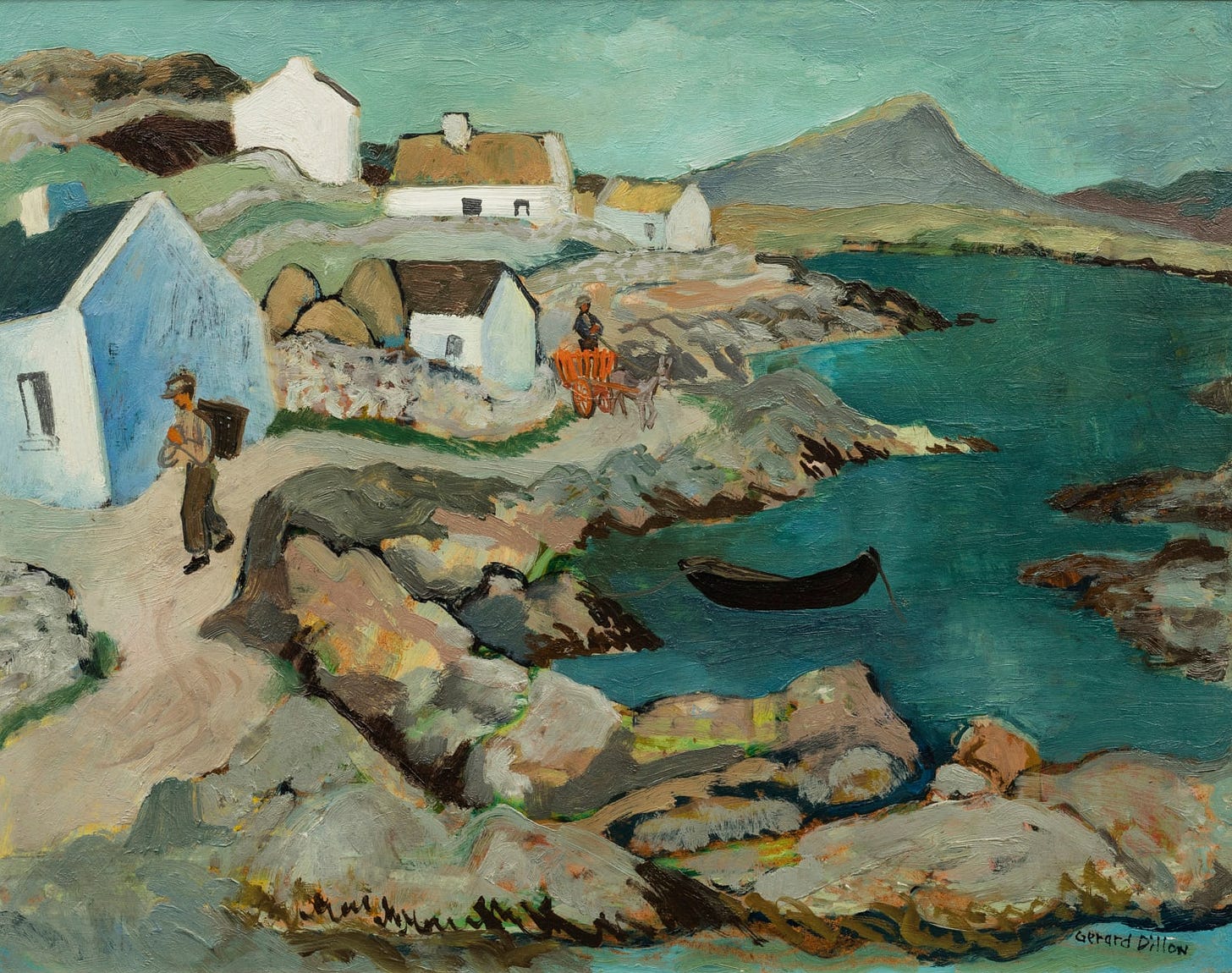

I don’t want to confuse anyone, I sail but am no sailor. I love the water but wouldn’t be considered a waterman. I am attracted to wooden boats for some reason but am no carpenter, but the mixture of poetry, mythos, Connemara, and time rotting away something made by hand, something about all of these things together drew me into the flame. And there is melancholy in the light and landscape of this corner of the world, there is sadness, but just like listening to the blues, there is what Oscar Wilde called “the savage beauty of Connemara.”

Connemara has drawn many. Orson Weles came in his teenage years, the missing years, and is said to have sold his soul to the devil for the gift of acting like the crossroads in Mississippi. He would tell people of purchasing a donkey and cart to carry him over the bogs and valleys of Connemara and used the place as an origin story when he finally got to Dublin. Wittgenstein came here to a cottage for a few seasons to escape, write and think. He said he could only think in the dark, and that Connemara was “the last pool of darkness” in Europe. Richard Murphy would live in the same cottage two years after Wittgenstein and go on to write a poem about Wittgenstein in Connemara, “The Philosopher and the Birds”. Louis MacNiece, Oscar Wilde, John Moriarty; the melancholic and introverted, “the mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time.” It is a place that is, in part, imagined and so is that much closer to the wells of creativity.

It is at the edge of something, either the landscape or tectonic plates of a chunk of land reaching from Cleggan pier to the Pacific, the Eurasian landmass. Or more so it is the edge of the Atlantic Ocean and the salty sea. These vibrations converging in one place creates a frenzy, a constant white noise of motion, zero of information content.

In the ghaeltacht regions there are strange connections with an ancient world not known in the history books. The traditional song and dance here is called Sean-nós (old style; pronounced SHAN-ohss). The swell of the sea pulses through the timbre of the speech patterns; vibrations in verse and undulations. You can feel this even more magnified when in a small room with a Sean-nós singer, usually singing with no instruments, a single voice like a column of air through a room, the melody and volume come and go in waves. Sean-nós singing is done with others, at home with a room full of friends and family, or in the public houses of communities. These are songs that need others, since their purpose is to share emotions and to inspire empathy. Songs here are used to communicate pain from death of a loved one, sadness from longing, jubilation from love and birth. Watching someone sing in the Sean-nós style is like feeling a hug, it is intimate, emotive, and delicate. Which is why when performing, at times, the singer will reach out to grasp a hand from a listener. Eyes closed, accessing the emotion and memory needed to fill the room, the hand is held in direct physical connection with another, a tether to the room as if the risk of being swept and overwhelmed by the memory in the song will take them away forever, one hand in the physical, one in the metaphysical. The two hands sway and pump in a slow circular meter with the song and the swell in the air. This is called ‘hand-winding’ and the audience member involved is termed the windáil, the winder.

There are other physical connections with Sean-nós, with the old ways. Song is affected by landscape. The landscape of the Aran Islands (a series of three shelves elevated between Connemara and County Clare in Galway Bay peopled by Irish speakers) is made of fractals and flows, it undulates. The distinguishing geological characteristic of the Aran islands is limestone, the surrounding regions either being water or granite, hard or liquid. Limestone, however, shifts and morphs and has memory, it is temporal. Every heavy rain washes a bit away, leaving a scar, a mark of the time. In this way it is colored by the swell of the waves in the sea, as they each come crashing, imprinting the shore.

The sea and the land do the same to the language of the region. The old Irish language, still spoken here, is scarred and imprinted upon by geography, by the landscape, agriculture, and aquaculture. It is also affected by story, and emotions. Dindshenchas is a group of Irish poems from early literature that were used to teach and pass on the idea of the names of places. These texts gave a history of the geography and the telling of context, of what happened with whom in this place and hence the name given to it. It is also the Irish word for topography, the concept of emotive history and mathematical mapping merging into one. A collop is a measure of a piece of land by its grazing-ability rather than its size. Or the village Tandragee in county Armagh comes from Tóin re Gaoith which means backside of the wind (because the village is on the leeward side of a hill, protected). Or a poem used to sail into a protected harbour on one of the Aran islands encapsulates the point of view of the majority of the culture: “Mant Bead ar Ghob an Chin; Teampall Bheannain ar na Clocha Mora” (“The Little Gap on the Point of the Head: St. Benan’s church on the Big Stones”). This is used by fishermen in small boats to negotiate a shoal off the island and it gives the listener the marks to look for while in on the approach into the shoal in order not to come onto rocks and sink your vessel.

The Ave Maria was in the region known as the home of the old ways, of the Sean-nós, Cois Fharraige, that south Connemara zone.

For the first few days we were in the village of Roundstone at a new hotel called Within the Village. An experiment in the idea of hotel. In travel, especially these days, the honest exchange of the human experience can be hard to find. Strange, as travel is an invitation to interact with other cultures and communities, but oftentimes walls are built around oneself in the name of comfort or security. I am talking about walled-in resorts and luxury hotels that feel disconnected from the place they inhabit. It is landed directly in the village and the name is perfect, it is Within, embraced, held.

It also was a place I had seen the Ave Maria in the water 20 years ago, used for tourists out of the bay. In my twenties I would guide groups on bikes through Roundstone, often having lunch with the group in one of the few pubs. I would come here in the pre tourist season as well to purchase maps from my late friend Tim Robinson, artist, cartographer, and writer. I would usually buy a whole season’s worth which was a large box of maps and books, then we would sit and have tea and talk about travel, math, and philosophy. He had a publishing business named Folding Landscapes and by that time he had created three maps and written two books on his life in the Aran islands, and had just published his first of a trilogy on life in Connemara. His office, and house were the same chunk of land at the end of a tip of a jetty, fish-hooked around a small inlet looking back at the twelve peaks of Connemara. Tims house was called “Nimmo’s Cottage” as this had at one time been the home of the famous developer Alexander Nimmo, the man who designed what is Roundstone today in the 1820’s. Prior to that there was no village, no roads, a path and a storehouse for illicit wool to be sold to French ships at a time when the English wanted all the wool. A place for smugglers and rebels. It wasn’t one of the ancient villages, those were down the coast. Our room at Within the Village looked out over Tim’s old garden. A serendipitous connection the boat seemed to stir. I would find out later the Ave Maria was sold to its current owner at the pub across the street.

After three nights in Roundstone we went inland towards the peaks to the Inagh Valley and Lough Inagh Lodge. Tucked in the Inagh Valley, sits a lodge, the old fishing and hunting lodge from the Ballynahinch estate nearby, a refuge. There are two sitting rooms as you walk in, a pub in the back, a dinning room to the left, and rooms upstairs and down the hall on the first floor. It is like my childhood home in that I can picture it in my mind and I know what it smells like and sounds like. This is the way I felt the first time I walked in, and many feel the same, like you have been here before, in some strange dream. Dominic O’Morain and Maire O’Connor, a brother sister team, run it and they are a joy. The farmers in the valley come down for pints at the end of a day and fill the back pub, and it feels and is very real. I’ve been from Tucson to Tucumcari, and this worn boot called Connemara can stir up nostalgia deep inside even if you’ve never been before. There is some prehistoric shared memory in this landscape.

Dominic and Maire come from Cois Fharraige, and when I told them my plans to seek out the Ave Maria they remembered the boat and knew the area and said the tidal beach in front of the house is where they had both learned to drive stick shift one summer as children. They vaguely knew the man who lived there but were hesitant or careful, almost giving me a warning not to bring my family with me when I go.

I grew up in small town Georgia in the southern USA. As a child I grew accustomed to a feeling of knowing when one was trespassing. I say this without any irony or trying to sound bombastic but there were times as a kid I was shot at if I was on someone else's land, shotgun buckshot mind you so not too crazy, but bullets and fear, so I recognized the unknown hesitancy in Dominics tone.

The final morning of our trip we decided to drive down to the coast in search of the house and in search of Ave Maria. The November light was low in the sky but bright, and slanted with long shadows, it was incandescent, almost haze, somewhat blinding, what I imagine the light those who describe close calls with death, a full enveloping light. It was technicolor and strange and I remember feeling like I was descending as we drove south to the Irish speaking coast, the Cois Fharraige.

There are bogs in southern Connemara and the roads that float over them roll and undulate like a vintage childrens ride. As you leave the twelveBens and the old mountains the land comes down to bog, part water, part salt, part peat, and many large rocks left over from the ice age; what geologists call Erratics; leftover formations from ice retreats which take their name from the Latin word errare ("to wander").

I knew the Ave Maria was there, I had looked on satellite images and had seen the boats form but I didn’t know what state it was in. We drove past Carna, following the coastal road, and at a sharp bend of the asphalt we stayed straight onto a sandy path, the kind that has grass growing in between the ruts. This road ended on a tidal beach. There were roaming Connemara ponies, we later would find out had jumped their fences to roam the low tide beach. There were piles of large kelp and dillisk in various pools along the shore, and small creeks flowing outward from the twice daily retreat of the pull of the moon. And surrounded by a short stone stacked wall were two boats in a back garden, identical to the pictures I had seen. The Ave Maria written on the side of one.

I was nervous and drove past the house to upper beach to park, my old shotgun southern fear. There was a dog on a rusty chain in the back garden that looked harmless but again my memories of Georgia property protection spurred caution. My kids and partner and I walked the beach looking at the horses and played with a rugby ball we brought, almost ignoring the boat we had been searching for, approaching it like a wildlife guide, not looking it in the eye. The kids were climbing up the kelp mounds. It was a November wind and chill but not too bad. Once a rhythm had set in with my kids I motioned to my wife that I was going to knock on the door of the house to see if anyone was home and as I walked from the beach towards the house, an old rusty car drove up into the driveway and parked and two people walked to the door to enter. The couple looked older and walked slowly but practiced, a route and path they had walked for many years. I was about 100 yards away as I watched them enter without noticing myself and my family.

As I entered the walled compound of the property the dog looked less guard-like and more tail wagging hoping for a pet. I started there. Then I walked to the door of the house. In the southeast USA I would call it a ranch house, one story, simple, much like the houses I knew growing up. Concrete and wood construction. I knocked on the door and waited. The door was thick so I couldn’t hear any signs inside of someone coming. The doors and walls must have been thick, on the coast, the wind and waves of the Atlantic coming to rest on the threshold. The door opened fast and a woman answered and said “and who are you” with little expression or emotion, cold and practiced.

I explained I was there to photograph and hear about the Ave Maria, that my family was here and we were interested in taking a look because we knew the history of the boat. I jabbered. The coldness broke and she smiled and said, “well come in for tea then and meet Marcus, he knows all about that boat”.