The first winter I spent in Ontario, the lake, as it often does, froze over. I decided to walk across it. My family and I spend part of our time in Toronto and part of our time on the shores of Lake Simcoe, an hour north of the city. In the winds and the snow there is a false sense of endlessness on frozen liquid. It is quiet, or more accurately it is filled with what sound engineers call broadband noise or white noise. The wind fills all and in its own way a sense of solitary noise makes it quiet. This is where the idea of the North began to present itself to me.

There is a vastness that is omnipresent in the landscape of Canada. ‘The North’, a seemingly endless expanse of wilderness, always present, always pushing down on the bottom line of the border with the US. In Toronto, people talk about going ‘up north’ for the weekend as both a geographic and psychological state. The playful weekend up at the cottage. But there is another North that looms past the cottages, past the roads and railways, a North that is far, wide, and large, like a sea, the tundra and taiga. Even the terrain merges with the sea at a point, in sheets of ice, where it becomes a mesh of land and frozen water, seasonal, tidal, and moving.

Glen Gould, the famous pianist and composer, spent the later part of his career away from the piano, instead focusing on the North as an idea. He grew up on Lake Simcoe. He was obsessed with the vastness, and with the way in which landscapes like that evoke the sublime, and end up focusing one’s attention on the self rather than the land. Landscapes that teach the skill and emotive state of solitude, a wonderfully powerful skill to have. He was interested with the way in which the North shapes part of the Canadian psyche, the culture. When you go North, you go into yourself. (If you have a spare 3 hours it is worth a deep dive into the counterpoint mind of Gould and his creations dedicated to the North: a radio program and a documentary series for CBC). I wonder if the frozen Lake Simcoe gave him the same slice it gave me of the sublime.

Gould also was known for his talent at performing fugues, a particular style of composition that used the musical technique of counterpoint. Counterpoint in traditional music consists of multiple melodic lines unfolding simultaneously over time. Each line maintains its own rhythm and structure while collectively forming a harmonious whole. This complexity presents challenges for both performers and listeners. With multiple voices occurring at once, a listener can only focus on one at a time. Likewise, a pianist must decide which line to emphasize, revealing connections in the music that might otherwise go unnoticed. To highlight a particular voice, the pianist must imagine it before playing. Interpreting a piece of music is ultimately a way of listening—understanding what to hear and how to hear it. The challenge of performance lies in knowing the desired sound and then striving to bring it to life through playing it.

There are multiple recordings of Glenn Gould where you can hear him humming in the background. He sings along, not always the melody, a playful hum that floats along with the notes, in the same way you can see blues and rock guitarists contort their faces, a physical surfacing of inwardness. Like Joe Cocker when he sings. His humming wasn’t part of the perfection in playing, it seems like it is out of his control, it comes out of him, he is in the music, controlled by it. When recording Bach variations, the sound technicians would have to bend and break around the hum, trying to shield the recording from the noise, but it was part of the whole of the performance. With Gould it was a dance, it was a fugue.

This is part of what I am seeking when I travel, some sort of feeling or flow that goes through me, is not controlled by me, but cannot help but follow or be steered; felt rather than planned. I have felt this on the lakes of the Shan State in Myanmar, in the subways of Tashkent, in the hills of Tuscany, that I am on a path, that I am humming along sucked up into a mad current, into fugue. Time seems to slip away and stretch when in solitude like that frozen lake. It is what meditation is in practice of, the goal of all those mantras. Perhaps this is why Glenn hummed when he played, his solitude, on some other plane, in mediation with some sort of musical North.

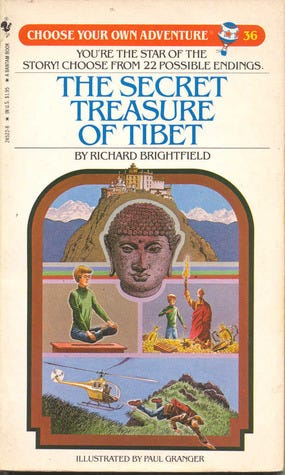

In the 1970s, writer Edward Packard started putting together a book inspired by bedtime tales he was telling his children, but he wanted a sense of agency in the weave, so he had moments in the book where you could make a decision as a reader, you could choose what the story was going to do. This was done by giving the reader a choice of flipping to the next page, or to some other page in the book, thus making each read of the book a different story with a different outcome, a different tone, a different melody. They were called “Choose your own Adventure” books and they left a mark deep and wide on me. The first one I picked up was Choose Your Own Adventure: The Secret Treasure of Tibet, and that, too, sent fractures down deep into my psyche that created a need and want to go to the Himalayas, to see and feel them as an adult. The impact was a sense of agency amidst a cornucopia of option, the idea of choice, freedom to decide and create a path, to hum my own tune, and that is what I have held all these years later, that I can become inspired by place and one day, stand up and start walking towards that place to see it myself. That I can choose my own adventure; it was a powerful analogy for my 8-year-old brain that changed the way I think and live.