how to paint in watercolors

Sidewalks and the paved parts of the urban landscape have alternative definitions in some cities. On the Silk Road after midnight, the roads and sidewalks become the communal domicile, as beds are dragged out into the streets to enjoy the cool breeze of the desert nights. Hanoi and Bangkok are two cities so dedicated to street food and eating that it is hard to tell where the streets end and the restaurants begin; walking from point A to B becomes an adventure diving through kitchens and dodging cars, like that eternal steady-cam shot from Goodfellas, when Ray Liotta and Lorraine Bracco walk through the dungeons of the Copacabana.

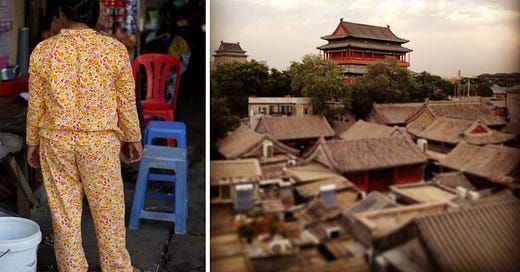

And in Shanghai, for years, certain city blocks were considered public living room space, so much so that it was not unusual to stroll your hood in your pyjamas, just as you would in your home. There was a whole fashion market for silk PJ’s to be worn on the streets, and for someone like me who prefers to be in his underwear as often as possible, it was Valhalla. Shanghai and the world have changed five times over in the past few years so it might no longer be; the world moves fast these days.

There was one street in particular that was so absolutely perfect it felt like it could have been a stage set from West Side Story rather than reality, a place where the objective and subjective merge into one, a little place called Jinxian Lu. The name translated means a few things but they all fit: “Kings Country” or “to offer as a tribute”. It was a small, one block road, filled with people in pyjamas and under-garments, a handful of trendy shops and small fashion-designer storefronts. And a little place named Lanxin family restaurant.

I’m not sure if it was legal or makeshift, but they were known for one main dish, Hong Shao Rou – braised and bronzed pork-belly simmered in ginger, garlic and the love of the gods. The culinary equivalent of Fabio’s biceps painted on the cover of some mid-80’s smut novel (pre pigeon-in-face incident). Here the lighting was bad, the floor was dirty, the noise abrasive, and the beer was warm. My nostalgia for this place is a permanent affliction – like tobacco for the once-addicted, I think about it daily. At the other end of the block was an American-style cocktail bar/restaurant where, when Chinese breakfasts became too much for me, I could sit down on the upper veranda, sip on a mojito and feast on eggs and sausage. In between these two spots, a lifetime.

The distinction between private and public was smeared by the heat of a humid city in the summer months, and the concept of personal space was bounded only by skin, rather than that imaginary bubble we carry around ourselves in European or American cities. The closest I have seen and felt a space similar to this in the Americas has been as part of a “Second Line” in New Orleans during a funeral – I think it has to do with hot climates and freedom from walls (for those unaffiliated with NOLA culture, a Second Line is the dancing troop behind the band, or First Line, during a communal parade sometimes done for funerals. Check out Les Blanks wonderful film “Always for Pleasure”).

In my memory, the street is living in a technicolor musical and makes me wish I knew how to paint in watercolors, if only to capture the sheen of the humid haze off the silk textiles clothing the people of Jinxian Lu.

When I lived in China there were days where I would become overwhelmed by numbers. Numbers of people around me, numbers of buildings in cities, astronomical numbers and metrics of a scale so grand I thought could only be science fiction. I would become overwhelmed with culture shock. Not unlike a blind-fold child in a pool yelling “Marco” waiting for the collective “Polo” answer to come but never receiving it, stumbling. There were times it would overwhelm me and I would find myself running through alleyways trying to find refuge from numbers, trying to find space and time.

Once, while visiting the Forbidden City, a place precisely set aside for both space and time, I was crowded by the ticket line getting in, a funnel of masses piling through the one gateway entrance to the verboden, thousands pushing and throbbing as we all oozed through the passageway ironically named the Gate of Supreme Harmony. I couldn’t take it anymore and started running. The only way out was up, and an ancient staircase showed itself to me so I took it, stairs dimpled with years of use. I saw no sign and no chain forbidding me from scaling the stair, I saw an out and I took it, leaving behind me thousands of domestic and international tourists sweating and pushing their way into a relic. As I climbed and left a world behind me, I remembered I had been told that Mao at times was known to scale this same stair in order to address his scripted crowds across the street in the famed Tiananmen square. Today it was empty.

I reached the top and there was a door. I still don’t know if it was the front or back door, but an entrance into a small museum that seemed, at least on this summer morning, to be little visited and little known. The lighting was golden soft, the staff quietly occupied, and I recall there was string music piped in a surround-sound system; a perfect antithesis to the huddled masses below, above the weather.

I learned later that this part of the Forbidden city and museum was called the Tower Gallery in the Meridian Gate at the Palace Museum. The exhibit was just being set up, and this was the first morning of the first day of a collection of porcelain salvaged from the wreck of the Götheborg, a Swedish East India Company ship that sunk on 12 September 1745 which had been filled with treasures from China. In a certain way, it represented a microcosm of the culture shock and misunderstanding I was in the middle of experiencing.

Porcelain, opium, silk, and tea. Western economies lusted for the numbers in China ever since the days Marco Polo had brought back porcelain to Europe. No one could figure out how it was made, which is why it became such a commodity. The etymology of the word tells us a lot about the European outlook on the world at the time.

Porcelain comes from the Italian porcellana, meaning “cowry shell”, a type of sea snail that was also one of the earliest forms of currency traded from Sri Lanka to London. Porcellana, in turn, comes from the word porcella, which means “young female pig”, some say because the shell looks like sow’s vulva (or belly, depending on who you ask). Porcella is a dimnutive of the Latin word porcus, meaning “pig”, which in the OG Proto-Indo-European language was porkos, which was rooted in the word perk, which meant “to dig”. As in pigs dig. And I dig me some etymology.

Which is a long way to say that Marco Polo came over to Asia, was impressed by this finely crafted pottery from a far advanced Asian culture, and named it (consciously or otherwise) after a sexual organ, much like my 6-year old likes to call his sisters artwork poo-poo art, a childlike, not-so-innocent jest. A lack of understanding and an assumption of superiority to another.

The Götheborg sunk coming into port in Sweden, less than a kilometre from the shore, giving rise to theories that the sinking was intentional to raise the price of porcelain. This was no small boat. This ship held 2,677 chests of tea weighing a total of 366 tons, 19 chests of silk, 11.4 tons of spices, about 100 tons of porcelain, plus rattan. The total value was equal to the national budget of Sweden at that time. The Swedish East India Company held Europe’s majority of porcelain, and to sink a large shipment created a run on remaining stock – creative destruction in world economies. The collection I was looking at were those bits found in the depths, cleaned and restored (and returned) and displayed on the 80th anniversary of the Palace Museum: Chinese earthen returned to Chinese soil.

What I didn’t get then, but started to slowly understand, was that my inability to step out of my culture and understand that the sense of being overwhelmed that I had been having since moving to China, had everything to do with me, and had nothing to do with China. I came to China, subconsciously, expecting certain things, and with a modus operandi built on appropriating things, like the cases of pottery the Gotheborg had loaded and lost. But what was really happening was something very different, I was shedding something off, starting to molt, at least in part.

When I descended the stairs back to China, I didn’t feel different, but something most definitely had changed.