In a churchyard on Boa Island there is a standing stone with two faces, a Janus god, namesake of January; old gods from ancient ways. About 4 feet high and a foot and a half wide, the faces on both sides are somewhat flat, and in between there is a divot where water gathers on the top, a small holy well where offerings are left behind, stone and water. In 1972 poet Seamus Heaney stood in front of this effigy and talked of forgotten ways, how nature was worshiped, and the old gods were scared off in a startle when the new Christian gods came. Worship went from the natural to the constructed, making the sacred sites indoors with vaulted ceilings rather than with the windswept hilltops worshiped before. The gods now lived in cathedrals instead of caves. I wanted to look the old gods in the face.

A few weeks ago I went to Ireland in an act I call research as it was, for many years, the best way to describe what I did. When I arrived in Dublin I went to visit a writer named Antony Farrell, founder of Lilliput Press. Lilliput Press lives at a crook of the road in Arbour Hill, Dublin, where Viking Place and Sitric Road converge. Next door to the press are stables where a neighbor family raises horses to race in a wonderfully Dublin tradition, an old touchpoint with nature amidst the constructed sprawl of the urban world. Inside Lilliput Press there is the perfect proportion for life; books, a large table, two perfectly sized chairs, and a sofa, all next to a window that lets the light in. When I came in to visit, writer Martin Doyle was doing the same, so the three of us sat and talked. This isn’t to name drop, only to express this well lit place is a natural gathering spot for lovers of stories and books. I told them both about my trip, and its purposes, that I was spending the next two weeks traveling the west coast of Ireland, hunting for echoes, caves, lost boats, and fringe sports. Antony then struck a chord in me that has vibrated since. He said “You are going on a Pilgrimage” and that really is what it was. Pilgrimage being the subject of the metaphysical, and that is what my trip was concerning. I was chasing curiosities and emotions rather than thread counts and Michelin stars. I wanted to know place, not through hotels or apps, but through landscape and feel.

There are fringe philosophies, and to think of landscape as having some sort of inherent value, some sort of oneness, a personality, might seem out-there, hippy dippy, tie dyed and barefoot, but I want to argue here that we have accepted much wider abstractions already and are just accustomed to them, or don’t fully understand their implications.

In 1757 Sir William Blackstone wrote in Commentary on the Laws of England that a corporation was a type of artificial person. It wasn’t the first time this idea was presented but it was a well documented one. For years the Catholic Church expressed ideas of oneness in the body of the church, as well as property ownership belonging to a parish rather than an individual priest, liturgies talking of the flock. A little over one hundred years later, a post civil war United States decreed the 14th amendment to its constitution, stating that no “state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” An obvious shift in legalities of slavery and human rights due to the recent war. With a vague echo of the idea of person already existing in the law of the land as both a living individual but also a corporation, this amendment was used as a legal tool for corporations for generations, often in conjunction with real estate ownership rights in a fractal post war USA. A case in 1882 of San Mateo County v. Southern Pacific Rail Road would allow for the opening of the idea that a corporation is a person in the eyes of the law, the concept of Corporate personhood. In 2010 corporate personhood really came into modern being through the court case Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission. A case that allowed for the corporate personhood idea to take a magnified form by saying that money is equal to speech, and corporations had the right for free speech, thus allowing corporations to pay for politics. This is a reduction of course. It is complicated, but in essence this is what happened.

Recently, a group of talented lawyers, musicians, poets, and writers, have used this legal fluidity of person in a wonderfully creative way, they have pressed the analogy into another mold, one that serves the old gods.

In February 2021, Mutehekau Shipu achieved legal personhood and shifted language and ideas. Mutehekau Shipu is also known as the Magpie River and is in Quebec Canada. It is not the first of its kind ( the Whanganui River in New Zealand was the first designated river with personhood in 2017) but the first in North America. From its sacred headwaters to the Gulf of St Lawrence, it is a whole, an environmental system, an ecosystem. It is recognized by the federal Government of Canada as a person with rights.

A central group working on this action is The More Than Human Life Project (MOTH), an initiative of the Earth Rights Research and Action (TERRA) Program at New York University School of Law.

In Ecuador (a place that changed its constitution to allow for the Rights of Nature) there is a rainforest called Los Cedros which is a particular ecosystem. In this forest a handful of musicians and poets gathered to compose a song called Song of the Cedars. The Forrest itself, writer Robert Macfarlane, field mycologist Giuliana Furci, field lawyer César Rodríguez-Garavito, and musician Cosmo Sheldrake created this song. The forest, with the rights of legal personhood, could be allowed to be credited as one of the composers of this song, a commodity which is sold and paid for with each click of the computer. Everytime spotify or youtube or apple music is clicked, a portion of funds go to the forest itself. Royalties are due to the composers and artists, and the legal framework, this kind of framework, allows for some very interesting avenues for conservation and philanthropic funding.

It is a shift in understanding, to look at ecosystems in this light. It is much more akin to the ancient ways, to the standing stones of Boa Island. It is using the legal language derived from capital obsessions to shine a light on ecosystems and the oneness of nature. A turning of an idea on its head, and in a way, a return to ancient ideas and relationships with nature.

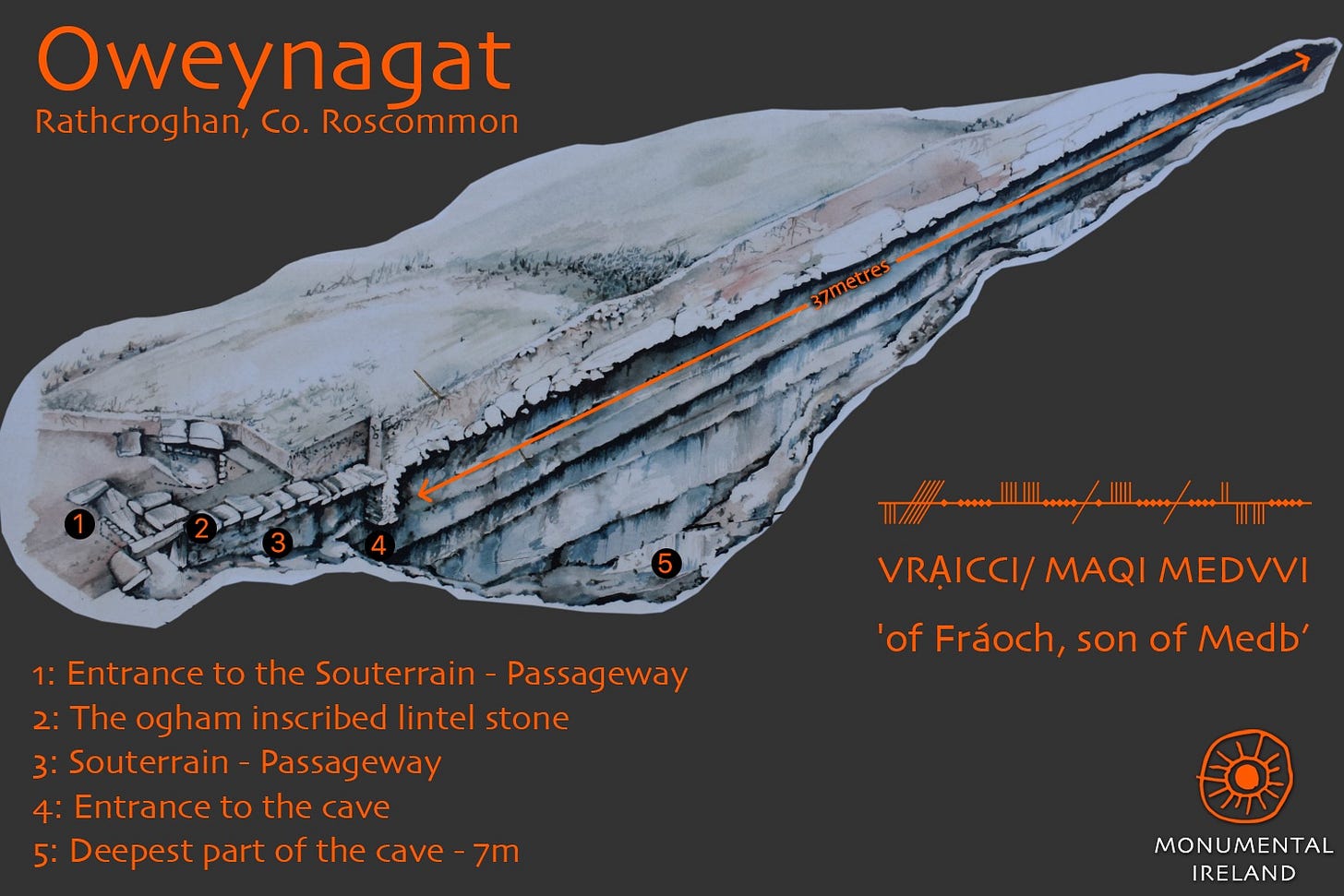

On the last day of my Pilgrimage I was driving south from Donegal back to Dublin. I stopped at Boa Island and looked at the stone gods. The area was thick with Hawthorn and old growth. The landscape had a gravity to it, depth, and it felt contained; it is an island on a lake. From there I drove south and took a detour to visit a cave, a subterranean gateway. Just North of the village of Tulsk there is a complex of archeological sites called Rathcroghan, the traditional capital of the Connachta, an old kingdom. The warrior Queen Medb was said to rule from here, and it is mentioned in many of the stories of early Ireland. Queen Madb ruled strong and was known as a warrior of great wit and strength. Under the tombs of Tulsk there is a fissure in carboniferous limestone bedrock, a pocket in the earth that predates any of the manmade sites; a cave. It is called Oweynagat and is thought to be a gateway to the otherworld.

There is a pagan ritual that happens here each year at the end of October when growth halts and the winter begins. In the tradition the distinction between the spirit world and the lived in world is blurred, this is called Samhain and is what later has become Halloween; this particular cave being the sociological origin of the holiday we now know by dressing as ghouls and consuming mass amounts of milk chocolate; it all started in this cave. The cave was also thought to be the birthplace of Queen Medb as well as the home of the Morrigan, a goddess of war and conqueror of fear. She takes her shape in many forms but often is seen as a black crow, and I have to say, I don’t know if this is a natural collecting place of crows, but the day I drove in I felt watched and studied and surrounded by crows. There were hundreds of them around. This was before I knew the history of the Morrigan so can’t be chalked up to the psychosomatic. It is thought that the spirits and gods leave the cave on this one day of the year and halt life and growth until the spring.

I don’t like caving, I am no spelunker, but there have been a few times in my life where I have spent time in caves and it has been haunting.

In my early 20’s I ran an outdoor education program at a sleep over summer camp in the southern Appalachians. There was an old copper mine on the property of the camp that we discovered one summer, a simple cave about 30 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 7 feet tall. You would crawl inside and it would turn to the left and down into the room, and there, once you were settled, you would find that there was little to any light. When we first found it it was the home of a family of turkey vultures, but they soon moved out due to our annoying visits. We then used the cave as a sensory deprivation space for sessions to teach campers how to use other senses and the importance of stillness and quiet. We would crawl in, sit down and turn off our flashlights for 1 full minute, then we would discuss what we felt and heard and saw. It was amazing what the mind would fill with full black space, when there is no light left, a busy mind fills it with things, leftover flashes while it calms down.

At the start, Oweynagat cave looked similar to my camp cave. It was a slice of an entrance under a tree, forcing one to bow to enter like a sanmon gate in zen temples. It, too, turned slightly to the left and then down into a large open space. My headlamp was not fully charged so it began to dull and I was forced to take out my phone to use it as a light, which is difficult in a crawlspace when you need your hands to move. I was scared and nervous. A month before I came on this pilgrimage I had called the local tourism office to ask about the cave. They mentioned there are times when the oxygen levels in the cave are low due to various factors. I was alone, and if I ventured too deep too fast and the oxygen level was too low then it would be dangerous. I slid into the main room only briefly and not that far and then turned around to exit. On a lintel stone over the second entrance after the slight turn to the left there were vertical lines scratched into the rock, Ogham lines, the written text of early Irish from 6th century.

The quick transition of space from farmland and fields to dark ancient cave is so complete and rapid that it is of no surprise to me that it was and is thought of as an auspicious place. It is a whole alternate subterranean world, just under the surface of things, yet drastically different from the outer topside world. It is a gateway into or out of something. Cathedrals are built as an imitation of the psychogeography of large caves. They force you to bow and feel humbled in the same way, a mimic of landscapes that predated all those Christian hymns.

In many ancient cultures the idea of soul is thought of as, in part, outside of the self, outside of the body, out there, to be sought after, to go out and to bump against, all these souls merging and mixing, a biosphere of spirit. You would go out into wilderness to find parts of yourself, parts of your soul, on a pilgrimage like Ulysses. It is part of something human in us all that is seeking, it is part of what drives us. For the majority of human history we were nomads, only shifting into settlements 10,000 years ago. Prior to that we moved about, our spacial relationship was different, we noticed different things in our surroundings, in our circadian rhythms. Perhaps this is what we hear calling, an echo of our nomadic selves that we recognize as we move about the globe, as we interact with each other, we see ourselves by looking our old gods in the face.